Oil was found in their soil. Everyone was excited. But rather than wealth, they got death. What is killing the people? Damilola Ayeni travelled to a Niger Delta village to find out, gathering evidence about the health and environmental dangers residents have lived with for 15 years.

Obituaries of young people litter Ebedei, a small village in the Ukwuani Local Government Area of Delta State. One has images of two boys standing side by side, and a quote: ”Death leaves a heartache no one can heal. Love leaves a memory no one can steal.”

“We can’t take the rate of death among young people any longer,” Nwajeli Sunday, the community youth head, says. He’s seated on a sofa in his living room, surrounded by a few men. “When I just came, it was very low, but ever since they started their oil operations, it has been nothing to write home about.”

Although the cause of the deaths appears obvious, villagers cannot ascertain it for lack of medical documents. “I cannot give the cause of the deaths since autopsies were not done,” Nwajeli continues. The long breaks between his words depicts one trying to be careful with words, like you and I know, but who am I to confirm?

Dr. Sam Edewor (not real name), however, gives a hint when asked about the impacts of gas flaring. He says, “Go to Ebedei. You will see. It’s too obvious.”

Dr. Sam is the medical director of a private hospital in Obiaruku, the Ukwuani LGA capital, which is a few kilometres from Ebedei. Since there is no hospital in their village, residents of Ebedei go to Obiaruku to see a doctor. And these days, up to 90% of them visit the hospital. This reporter followed their footprints.

An attempt to get further information from Dr. Sam is unsuccessful on the first meeting. Among other tasks, he is getting ready to dress a patient. He, however, reveals that his patient had an accident at a gas plant in Ebedei while trying to load oil into the tanker. Dr. Sam calls the incident “one of the effects of gas flaring”. Later, he calls it “burns from the gas plant”. But his message is clear: Ebedei is bleeding, and oil is its blood.

Old Ebedei Is No More

After 21 years in Lagos, Nwajeli went to live in Ebedei. His father had decided to relocate to his homeland to start farming. Ebedei at the time was a scarcely visible settlement. Its only plea was its fling with nature, and that was enough to cheer anyone coming from Lagos. Unlike the fog in Lagos, fresh air was abundant in Ebedei. Tracts of green vegetation covered the soil. The village stream beckoned on children, and dwellers smiled greetings to one another.

Life can be good in a village. Something belongs to everyone. You can bite into fruits just falling and throw them away. While the rush and push of the city shields anyone from seeing anyone else, everyone belongs to everyone else in the village. That fine rural life was, however, short-lived for Nwajeli. Oil was soon discovered in Ebedei. It would rip the village of its charm, and the people of their innocence.

Initially, the discovery of oil enlivened the people, as they saw the prospect of basic amenities and general improvement in their economic condition.

“We were very happy because we knew that wherever there’s oil there’s benefits,” says Nwajeli. “We expected good roads, pipe-borne water, employment, infrastructure, etc.”

Gas Flaring, a Threat to Life

All that is needed to establish the dominance of gas flaring in Ebedei is a walk round the village. Like a flag, fire waves in the air, shining on the streets like a full moon. It burns 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The heat and hazardous particles from the fire, and the muffling flavour of burnt gases mess up the small village.

“That fire is seen everywhere in this village,” a young man who identified himself as Joe says.

Gas flaring violates the natural rights of human persons to life and dignity, as a polluted environment is a threat to life. Acknowledging this, several legislations sought to end the practice in Nigeria. One of them is the Petroleum Industry Governance Bill, 2017, which outlawed gas flaring. It sailed through the two chambers of the National Assembly but was denied assent by the president. Gas flaring was initially prohibited in 1984, following the birth of the Associated Gas Re-Injection Act. The fadeout time, however, kept changing like the seasons until it was put at 2020 two years ago. It’s a year past the deadline now, and nothing has changed.

Cancer, Internal Heat, Insomnia, Difficulty Breathing

The go-to for many Ebedei patients is Spring Clinic, Obiaruku. The resident doctor, Samson, says breast cancer is common among the people.

“There are many cases of breast cancer around here,” he says. “Back then in [medicine] school, when we asked these patients of their locations, a lot of them said Umutu, Ebedei and Okomu. We found out that these places are close to flaring units.”

Several studies have linked gas flaring to cancer. Flares are known to contain over 250 toxins, some of which are carcinogenic. As reported by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, exposure to flare smoke can prompt chronic bronchitis, aggravated asthma, decreased lung function and premature death.

Some of Dr. Sam’s patients have complained of internal heat in recent times. According to the doctor, internal heat is a strange medical condition. Its pal in the medical glossary is hyperthermia, which Medical News Today says can result in organ failure or death. It’s a group of medical conditions which “occurs when the body’s heat-regulation system becomes overwhelmed by outside factors, causing a person’s internal temperature to rise”.

Dr. Sam also reveals that many young people in Ebedei find it difficult to sleep. They have not only been complaining of insomnia, but also constant headache and runny nose. “If you don’t sleep,” says the doctor, “you will have a headache.”

Constant noise, heat and light from flaring units may result in sleep deprivation, which can become insomnia, according to medical literatures. This was Goodnews’ experience when he lived in Ebedei a few years back. He believes he found sleep difficult because of the steady heat coming from surrounding flares.

Goodnews, a motorcycle rider, can tell a difference in his breathing the moment he steps into Ebedei. “The air here is heavier,” he notes. “It feels like someone is sprinkling dust.”

Several researchers have raised concerns over air quality. Endocrine dysfunction, reproductive disorders, and rheumatic diseases have all been linked to poor air. In one of its records, the World Health Organization (WHO) says up to seven million people die every year from diseases related to air pollution.

Acid Rain Suspected

People began noticing changes in their roofs a few months after the commencement of oil operations in Ebedei. Nwajeli recalls how zinc sheets quickly took on a new colour. “All roofs that were shining in those days became brown,” he says.

Another villager narrates how people took down their heavily damaged zinc sheets barely six months after roofing. Generally, acid rain damages roofs in places close to factories, gas plants, and power plant smokestacks. Corrosion of zinc sheets results from the emission of sulfur dioxide, methane, and other flare compounds that make make up acid rain. This polluted rain is equally harmful to health. A World Bank report related it to cancer, anaemia, renal dysfunction and some neo-behavioural changes in humans.

While, for fear of acid and flare particles contamination, some residents have since ditched the village stream, others continue to drink from it for religious and/or cultural reasons.

“All of us used to drink from the stream,” says Joe. “Even now, some people still prefer water from there.”

A Blaze and a School — ‘The Students are Ignorant‘

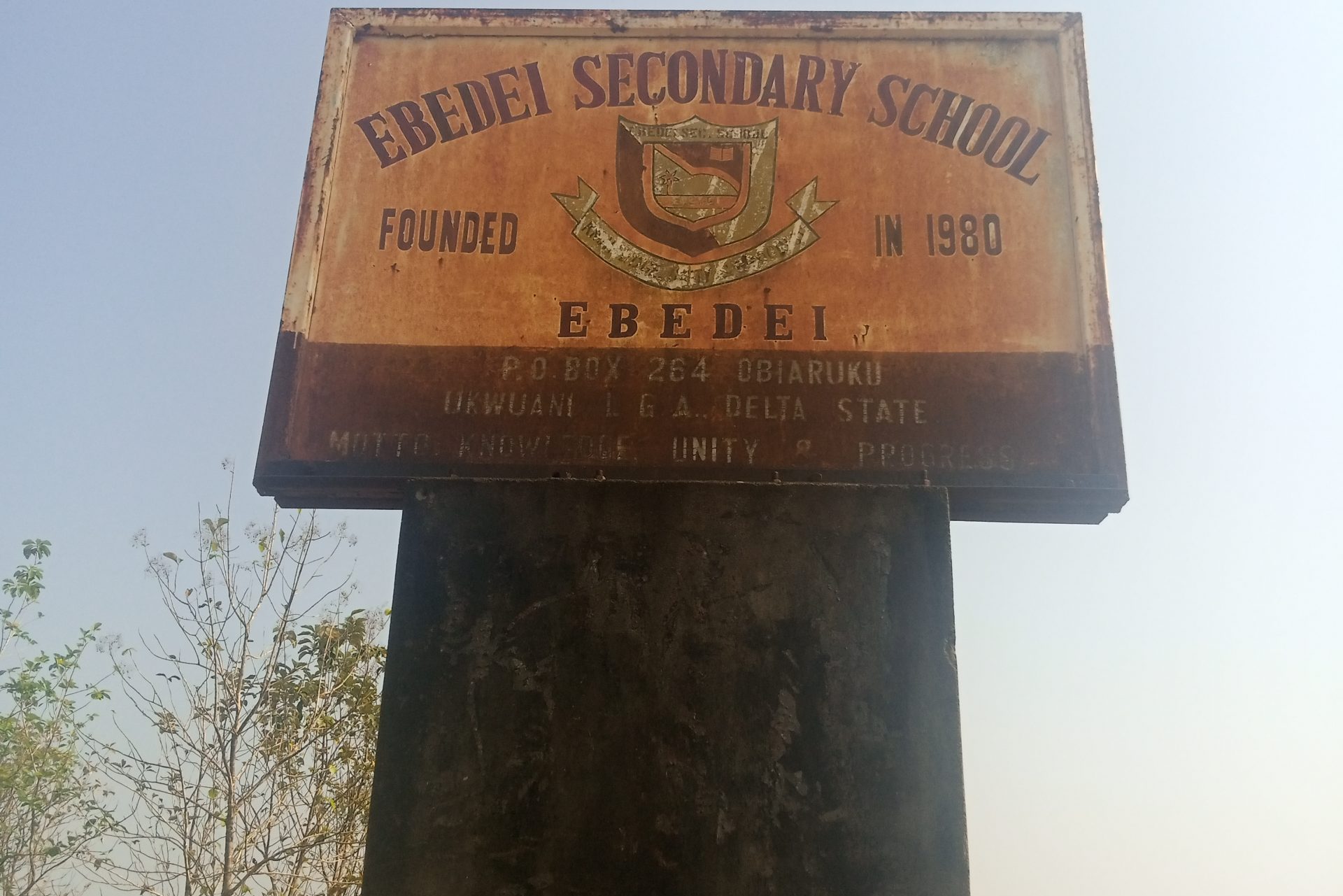

Ebedei Secondary School, which is home to tens of teachers and an estimated 600 students five days a week, is located in front of PNG Gas Processing Plant. From the combined effects of a flare and the sun, the school gate feels like the gate of hell. Heat burns the skin, and the flare is as loud as the sea. The windy-stormy sound of flares is heard even in the vice-principal’s office. It’s a mystery, how learning takes place in such an environment.

“It distracts us,” the vice-principal laments. “Sometimes it’s very high. Other times it goes down. Often, I ask myself what’s happening before remembering it’s the flare.”

Section 17 of the Petroleum (Drilling and Production) Regulations forbids oil-based activities in any area put to public use. Also, the School Siting Guidelines of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency prohibits siting a school near an industry or any source of environmental pollution. Interestingly, Ebedei Secondary School occupied the area first. It was established in 1980. The PNG Gas Plant started operations much later, in 2016.

With such close proximity to flares, one will expect that Ebedei Secondary School is poorly populated, but this is not the case. “Enrollment is not affected, yet,” the vice-principal says. “The black man can adapt to any situation. More so, the students are ignorant.”

Produce Has Gone Down

The effect of flaring on farming is common knowledge in Ebedei. Many residents agree that harvest is no longer what it used to be years back. “Ever since they started gas operations,” says Nwajeli, “produce has gone down.”

The vice-principal of Ebedei Secondary School tells a similar story about the school farm. He says, “The maize will grow very tall, but without cobs. Before, the cobs were very big.”

Bad harvest in an oil-rich community may have roots in the intense heat coming from flares. Heat alters the process of nitrogen and organic matter formation in soils. Several scholars also believe the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of soils close to gas flaring may reduce significantly, and this has implications for the fertility and nutrients of such soils.

After uprooting three stands in his farm near PNG Gas Processing Plant, all Nwajeli gets won’t add up to half the size of an average cassava tuber. One is as tiny as a drum stick. Another looks like a hand-bell clapper.

Cassava Like Poison

This reporter returns to Lagos with the tubers from Nwajeli’s farm, and then to a laboratory. A careful analysis conducted by a registered public analyst reveals the presence of heavy metals in the following quantities: 0.84mg/kg, lead; 19.68mg/kg, zinc; and 0.20mg/kg, chromium. Being well above the EU and WHO set limit for each metal in plant tissues, these figures imply toxicity.

A WHO report linked lead toxicity to increased risk of high blood pressure and kidney damage in adults. Exposure to chromium irritates the lining of the nose and sparks runny nose and breathing problems like asthma, wheezing, cough and shortness of breath. In Ebedei, many farms are sited close to flares, and crops can easily pick up dangerous metals for human consumption.

Further analysis reveals that polyhydric aromatic hydrocarbons are present in the cassava samples collected. Dibenz (a, h) anthracene, one of the hydrocarbons found has been determined by the U. S. Department of Health and Human services to be an animal carcinogen. Other hydrocarbons found include naphthalene, 2-methyl, acenaphtene, and indeno [1, 2, 3-cd] pyrene. Naphtalene destroys red blood cells and triggers a problem called hemolytic anemia, especially in children. Acenaphthene causes kidney, liver, and lung damage, while indeno [1, 2, 3-cd] pyrene has been linked to allergic lung inflammation and asthma.

Everybody eats cassava in Ebedei. An average resident eats it in one form or another at least once in a day. One can imagine the extent of the damage contaminated cassava tubers can cause residents.

Acid Rain Confirmed

Laboratory analysis reveals that the two most natural water sources available to the people are contaminated. Rain and stream water samples collected show acid concentrations of 15 and 24 parts per million (PH value of less than 3) respectively.

Among other factors, high acidity of the stream may have been caused by the acidic rainwater. Acid rain falls directly into a stream and also flows in through the soil, leaching aluminum from soil clay particles into the water.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the pollution that causes acid rain can also create tiny particles that get into people’s lungs to cause health problems or make existing ones worse.

Reacting to the findings, NnimmoBassey, a Nigerian environmentalist and Director, Health of Mother Earth Foundation, says, “It is not a surprise that life expectancy of the people of the Niger Delta is among the lowest in the world. Key among the impacts of gas flaring on the environment is the fact that it spews a cocktail of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, sulfur and nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere, thus contributing to climate change and associated harms.”

Flare Gases Aren’t Just Waste

As alternatives to flaring, several pathways have been identified for the use of natural/flare gases in driving economic growth. They can be converted to electricity or purified and stored up for industrial and domestic purposes. After launching the Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme in 2016, the federal government declared that the new body would help meet its 2020 flare-out target by exploring these alternatives.

However, an investigation by On Our Radar, a London based non-profit, revealed that rather than reduce, the number of flares in the country increased in the two years that followed. This may have resulted from government’s hesitation to bear the upfront implications of commercialisation. Government’s revenue largely depends on oil sales. A fair share of Nigeria’s oil fields, meanwhile, has associated gases. Any effective commercialisation or flaring ban will require investments in new institutions and facilities, and this will initially reduce the revenue generated from oil. This is the risk the Nigerian government may not be willing to take.

Nigeria today ranks among the seven countries that flare the most gas globally, and the Niger Delta is the most polluted region in the world.

To What End?

The initial glee over the prospects of basic amenities deflated as oil companies failed in their moral obligations to atone Ebedei community with strides of tangible social and economic development. For over 15 years of their presence, not a single hospital has been delivered. The only health centre also lacks facilities. There has been no blink of electric light for over one year. Everyone wakes and sleeps in the dark. The soil is now so poor that young people flee to farm elsewhere.

Above all, the trademark rural life of love and unity seems to be under threat in Ebedei as oil companies deploy a divide-and-conquer strategy to advance certain objectives. “They will give some people money and still be the one to leak the secret, just to cause a problem here and there,” Nwajeli reveals.

Fear in the Air

The atmosphere in Ebedei is one of fear and suspicion, where people are cautious of speaking with strangers. This culture of silence may have roots in the series of oppression and harassment served to oil-rich communities over the years. In 1999, Nigerian soldiers invaded Odi, a predominantly Ijaw community in Bayelsa State, killing tens of residents following a conflict over rights to oil resources and environmental protection. Four years earlier, nine activists, including the renowned Ken SaroWiwa, were framed up and executed by the Nigerian government for speaking up against the series of environmental degradation caused by the activities of oil companies in their land.

But courage is fire.

While, like a child told to never talk to strangers, many Ebedei residents dodge a conversation with this reporter, Nwajeli speaks and speaks again. He belongs to a group of brave young people who will stop at nothing to demand justice for the community. They’ve learnt to neither complain to the seemingly complacent Nigerian authorities nor hit the streets with placards. Security agents, in their view, may take advantage of a protest to unleash mayhem on innocent villagers.

“We use the law to face them,” Nwajeli says. He had just returned from the court when he speaks one last time. “The case is between one party from the community and the oil companies, Power Gas and Platform. It is about the way the companies are treating my people.”

Asked if the possibility of being persecuted or killed will ever hinder him from pushing further for justice, Nwajeli gives an emphatic no. “People still remember Ken SaroWiwa till today,” he says. “If anything happens to me, I will be remembered.”

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.