There was no visible media presence. The hall at Fountain Hotel in Ado-Ekiti was filled with petitioners and their lawyers, many of whom had come to seek justice. Justice meant compensation for their damaged properties. For others, justice meant freedom. At the back of the hall, two men were chained to each other. One was older, 49 years old. His name, Oluwole Edward. The younger one, Elegbeleye Adetomiwa was 36 years old. They were chained at the hands, and joined by their quest for justice, and freedom. Their faces carried the expression many Nigerians have when dealing with power: scepticism. Would the panel help their plight? Two correctional officers sat at both ends of the row, securing their prisoners. Occasionally the officers whispered instructions. Their interaction reminded me of Asa’s Jailer. You’re a prisoner too, Mr. Jailer.

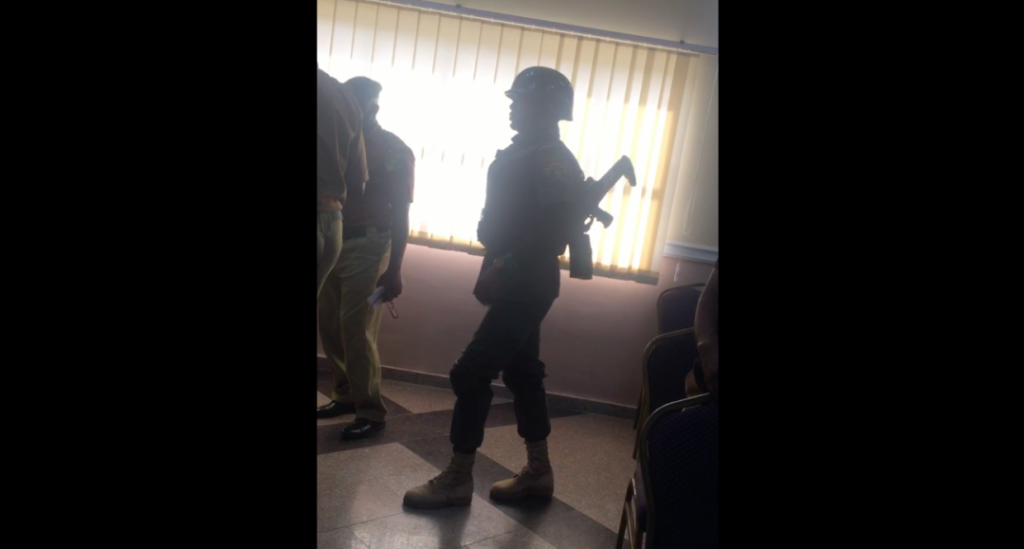

Outside the entrance of the hall, I saw a young sprightly police officer, fully kitted with a bullet proof vest, knee pads, and a rifle I couldn’t recognize at the time. He looked more equipped for a peacekeeping mission than a panel. I would later send a picture to a security expert who informed me that the gun was a Pindad SS1, an Indonesian weapon manufactured in 1991. A quick Google search lists Nigeria as one of the users of the rifle. It’s not a popular rifle, the security expert confirmed. The police officer was here to secure the prisoners. The hall was filled with conversation. Familiar faces greeted each other, and strange faces maintained polite silence. Policemen whom I suspect had a case to answer before the panel occupied a full row. A woman who was unable to find a chair on that row went to the other side of the hall. The man beside me held his car papers and petition letter; his car was destroyed by hoodlums during the EndSARS protests. The petitioners were old men, young men, young women, old women, educated, uneducated. They had all come with the hope that they would get justice.

AS THE COURT PLEASES

At 12:05pm, three loud knocks came from the door in front of us. Silence fell on the hall, and everyone, including the two prisoners who were still chained to each other, stood up as the panel walked to the table. The Chair of the panel, Justice Cornelius Akintayo, and the rest of the panelists bowed slightly before they took their seat. Behind the panel, a large banner announced: The Ekiti State Judicial Panel of Inquiry into allegations of human rights violations against police officers, including the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) and other persons. This was the ninth sitting — on November 20, 2020. Justice Akintayo asked for the first case to be called. He spoke like a man for whom authority came naturally. The lawyers who presented their cases, in response to what he said, always responded with, “as the court pleases”. Other times, they would speak and wait for him to say, “go on”.

The first case was adjourned to December 1. Justice Akintayo asked that another case be called. It was between the Nigerian police and Yetunde Bamidele, the woman who couldn’t find a chair. Her car was seized by the police and kept at their station. When hoodlums started attacking police stations, her car was destroyed. She was not the only one with this complaint. Her lawyer had not served the police, and Justice Akintayo adjourned the case to December 1. Her lawyer responded, “as the court pleases”.

Another group of petitioners whose shops were looted were asked to come with further evidence. A young man recording the proceedings was asked by Justice Akintayo to stop.

“We have an official camera man who documents what is going on here,” Justice Akintayo said.

The only camera man I saw was a man in brown suit and tie carrying a phone around taking pictures occasionally. There were no videos on social media. No detailed account of the panel proceedings was captured on the Twitter page of the Ekiti State Judiciary Panel. And unlike Lagos, as the cases of the petitioners got adjourned, the hall got emptier.

Justice Akintayo wanted to listen to the case of the two men who were brought in from detention, so he adjourned and adjourned. In some instances, a lack of witness or preparation by counsel led to the adjournment of cases.

When Justice Akintayo announced that the panel would be listening to the case of the two prisoners, a woman at the other end of the hall did a sign of the cross, her head looking up. The woman beside her was equally relieved. Both were the wives of the two prisoners. Their husbands were taken away from them by SARS.

FARMER PARADED AS ARMED ROBBER — BUT HE CAN BE FREED FOR N500,000

At 11:55 pm on January 8, 2020 Elegbeleye Tomiwa, a farmer, was sleeping at home when he heard loud knocks on his door. He hesitated to open. He was inside his house with his wife, their child and his brother who slept in the living room. Tomiwa looked at his wife and told her it seemed they were about to be robbed by thieves. He told the men at the other side of the door that he wouldn’t open until they identified themselves. The response was more knocks to the door and a command to open. Immediately he opened the door, eight men burst in and slapped his face. His wife was also slapped and handcuffed.

“Who were these men?” His lawyer asked at the panel proceedings.

“SARS from Ado-Ekiti.”

The eight SARS officers took his three phones, two androids and a Nokia and went through the phones. They then proceeded to demand for money after they had taken the N7,500 he kept at home. At the panel, as he narrates his story, he is overcome with emotions. At every point, his lawyer urges him to speak slower to enable Justice Akintayo write what is being said. But that night seems to replay itself in his mind, and he talks faster, unable to hold back the memories.

“They took everything. They scattered everything, including my clothes. I begged them to allow me speak to my wife for the last time before they took me away,” he said in Yoruba, his preferred medium of communication.

The panel provided an interpreter who helped translate the questions his lawyer asked. The act of begging to speak to his wife for a last time symbolized a finality to his hope to live. Wherever these men were taking him to, whatever they were going to do to him, he wasn’t sure he was going to live for the next few minutes, hours, days, weeks, months or even years.

The SARS officers used the butt of their guns to hit the ceiling of his asbestos roof. What they were looking for, he did not know. He had just harvested some crops from his farm. That was the only thing of value in his house. He was taken from Ikere-Ekiti to Ado-Ekiti, a distance of 19km, a 36-minute drive. But this was the beginning of his horror in the hands of SARS.

At the panel, Tomiwa maintains his innocence. “I did not do anything,” he repeats more than once, unable to fathom why he has been in custody since January 8, 2020. That night, when he reached their headquarters, his hands were tied on a pole, with his legs dangling while he was beaten.

“What were you told to do so you could be released?” His lawyer asked.

“They asked me to bring N500,000. They beat me with a rod. Here are the scars,” Tomiwa said as he removed his shirt, crying. He walked to the panelists, almost like an exhibit of suffering. The official photographer came with his phone, asked Tomiwa to turn as he took pictures for social media. This was the most emotional I had seen Tomiwa. An emotion that the counsel to the police later said was staged for the panel so that he would be pitied and released.

Tomiwa had told the SARS officers he was a farmer and his wife was a recent graduate who did petty trade, there was no way he could raise N500,000 ($1,300). The torture continued until the police had to get him medical treatment at the Nigeria Police Medical Service at Oke-isa.

He was tortured with a pressing iron, each time begging for his life. On February 11, 2020 he was brought to court and was charged with armed robbery. Two days later, he was taken to prison. His case, which is currently at the High Court, is still being heard. Tomiwa told the panel he needed medical check-up because he was experiencing breathing problems, a result of beatings he received from the SARS officers.

TOMIWA NAMES HIS TORTURERS

“How will I ever forget those who tortured me?” This was Tomiwa’s response to the counsel to the police who asked him if he remembered those who tortured him. “Deji Adedeji, Odetola Ogidan, Marcus, Omoh, and one lady Catherine,” he listed out their names.

“Witness, is there any date on your body to show that this was the date the tortures happened? I put it to you that the scars have been on your body since,” the counsel to the police said.

It was a question which seemed to irritate those in the hall. Justice Akintayo allowed the question to stand.

“You are asking him that he should have submitted his body for more torture to have the date written on his body?” The defence counsel stuttered a reply. It seemed Justice Akintayo himself was bewildered by the question. And as if to register the absurdity of the question, he wanted Tomiwa to answer.

“My wife knows this was not how my body was,” Tomiwa argued. And when the counsel to the police said Tomiwa was charged for armed robbery and was on a list with six others, he argued he knew no one on that list.

“I still don’t know what I did till today,” he said.

The prison warden beside me explains what the various initials on the prison document mean. He tells me that armed robbery in the afternoon and armed robbery at night are treated differently under the law. He also explains that Tomiwa had been admitted into prison on February 13, 2020 and his case adjourned to February 28, 2020. He laughs at the questions the counsel to the police asks. They are questions that put more doubt in the whole structure of the police system.

For the past 11 months, Tomiwa has not slept at home. As he leaves the podium after giving his testimony, Oluwole Edward, the second prisoner, prepares to take the stand. It doesn’t escape my mind how these two men, poor, and helpless are part of the exhibits of Nigeria’s failed judicial system. Oluwole has been in prison for the past two years.

SORO SO’KE

The two wardens have their nose masks just under their nose. I notice that their uniforms are neat. Oluwole Edward stands up when his name is called. He is wearing a polo shirt and a jeans. The Yoruba interpreter returns to the stand to translate. The oath is taken in Yoruba, one hand on the Bible swearing to tell the truth and nothing but the truth.

Oluwole used to sell alcohol and run a beer parlour until one evening on January 2, 2018 when three SARS men in a golf car stopped in front of his business place with their guns raised, threatening to shoot him and the customers who were drinking. From Ilogbo-Ekiti, he was taken to Ado-Ekiti, a journey of almost an hour, covering 34 kilometres.

While giving his testimony, Oluwole speaks in a low voice, prompting the interpreter to tell him to soro so’ke, a term that has come to not just mean speak up, but also confidently, for justice. During the #EndSARS protests, it was used to urge people to speak truth to power. Power in Nigeria, like everywhere else, always fights back. Oluwole was fighting for his innocence.

“They burned me with iron,” he tells the panel as he shows them scars on his hands and legs, saying he suffered in the hands of SARS. Just like Tomiwa, the SARS officers also stole the money he had in his shop at the time.

“They took my N8,200, drank my beer, and took my phone,” he explained.

N120,000 OR TORTURE

When the torture began, the SARS officers asked him to bring N120,000 ($315) to beg their boss to release him and stop the torture. He had no such money, and he was detained for a month before he was taken to court by a different set of policemen.

Though he didn’t know the name of the two other SARS officers who tortured him, he mentioned Omoh as the third. Tomiwa had also mentioned Omoh as one of his torturers. But Omoh was nowhere to be found. And just like Tomiwa, Oluwole was also charged for murder and armed robbery. The charge is a consistent modus operandi by the Nigerian police which knows that the magistrate court is not competent to handle such cases. The magistrate court usually adjourns the case and asks the accused persons to be remanded in prison pending when the case would be taken to the High Court. Between the time of waiting for the high court to give a ruling amidst the many adjournments that take place in the Nigerian courts, time ticks by. Justice becomes harder to find, and many more innocent people, unable to pay off SARS officers are thrown into prison on armed robbery charges. It is a circle that doesn’t seem to stop.

On June 13, 2018, Oluwole was admitted into a prison the warden shows me. And he was taken to court again on July 20, 2018 for trial.

“I am being punished for a crime I didn’t commit,” Oluwole said to the panel.

When the counsel to the police said “Witness, you were not tortured at all by the policemen”, Oluwole’s response was an emphatic no. Wasn’t he the one who suffered under the police he asked back.

“I suffered,” he said in a way that made those in the hall laugh. And when the counsel to the police again stated his claim, Oluwole retorted his response, “I suffered very much.”

Both Tomiwa and Oluwole did not request for financial compensation when asked by the panel what they wanted done. They both wanted their cases investigated and get their freedom. When I spoke to a lawyer who came to witness the proceedings, he said the panel could not do anything about a case that’s already in the high court. Was this an exercise in futility? Tomiwa’s lawyer argued that he was at the panel to seek justice over the brutality he suffered under SARS officers as indicated by the panel.

When their case was adjourned, the young police officer came into the hall. He had been outside all along. The correctional officers chained both prisoners as the panel came to a close, and walked them outside the hall. The wives of both prisoners walked towards their husbands, exchanging conversation, giving assurances and reassurances. As Oluwole walked, his hand chained to Tomiwa, he stopped, realizing that Tomiwa was still talking to his wife. The two women, squeezed something into the hands of the correctional officers. One of the correctional officers looked at his palm, nodded, and gave some assurance to the women. The police officer, as if in a rush, herded the men out of the hall, separating them from their wives who saw their husbands taken from them again. Oluwole’s wife wiped away her tears with a handkerchief. It was like a parting she had to relive over and over. A trauma that had become malignant. How long would she watch her husband stay locked up? How many more years would the court take to listen to his case? How much money and stress did she need to endure?

For the poor, justice seems to never come. A 2016 report by Amnesty International stated that the majority of the victims of torture in SARS custody are poor and unable to hire legal representatives. The report further noted that the Nigerian justice system failed to both prevent and punish torture. Despite Nigeria’s membership of international human rights organisations, and the Nigerian Constitution prohibiting torture according to Section 34(1)(a), which states that “no person shall be subject to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment”, “everyday practice is inconsistent with the constitutional provision prohibiting torture,” according to Amnesty International. The EndSARS protests which demanded for accountability of the Nigeria Police led to the formation of judicial panels across the country.

Tomiwa and Oluwole were not only subjected to inhuman treatment and torture, but have also been imprisoned for long. Cases in courts in Nigeria can last for decades as the accused awaits justice. Nigerian prisons which are many times overcrowded, continue to be occupied by prisoners who are unable to meet bail, or are waiting for their time in court. With every passing day, the families of Tomiwa and Oluwole continue to hope and pray that their husbands would be released from prison.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.

2 replies on “How Ekiti SARS Officials Paraded a ‘Farmer’ as an Armed Robber — Then Asked Him for N500,00”

What a sad story. I ask myself when and how Nigerian wil come out of this mess

This is very detailed, Nigeria correctional Centre is crowded with those that are awaiting for a trial, I got to know this during my visit to one of the Correctional centre in Lagos State . Heard Bail is free in Nigeria,so how come , They still request for money to be bailed ? Guilelessly,I am fed up of my country . These officials don’t read and notice that people are aware of their atrocities .