Alice Paul was born in 1964 in Badarawa community in Kaduna North Local Government Area (LGA) of Kaduna State. That was four years after Nigeria gained independence from British colonial rule.

When she got married later in her mid-20s, she moved to Ungwan Yero, a Christian-dominated community that exists as a dot in a circle of overwhelming Muslim settlements in the Muslim-majority Kaduna North LGA.

Yet, Paul and her family, who are Christians, never had a reason to feel unsafe or discriminated against by Muslims in Badarawa and Kaduna North LGA.

“We lived in peace with them. During Salah, they would bring food to my house, and during Christmas, I shared food with them,” Paul, now 57, said. “There was mutual understanding between the Muslims and us.”

In Kasuwa Magani, a Christian-majority community in Kajuru LGA, Southern Kaduna, Shafiv Hassan, an imam, said Christians used to show love to Muslims who were the minority.

“Our relationship was very cordial. We used to do everything together. There was no difference between Muslims and Christians, except during prayers,” the 47-year-old, who is also the Chairman of the Jama’atu Nasril Islam (JNI) in Kajuru, said. JNI is the umbrella body of Muslims in Nigeria.

Kaduna State, the capital of the defunct Northern Province during colonial rule until post-colonial 1967 when Nigeria replaced its regions with states as the federating units, is nearly evenly split between Christians and Muslims. Testimonies of peaceful coexistence and tolerance used to cut across the state.

HOW THE STORY CHANGED

Kaduna is geographically divided into north and south. Muslims are the majority in the north while Christians dominate the south. Most of the Christians in Southern Kaduna are from over 30 different ethnic groups and are predominantly farmers.

Living among these ethnic groups as minorities are members of the Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups. They are predominantly Muslim nomads and traders who settled in the south over a hundred years ago.

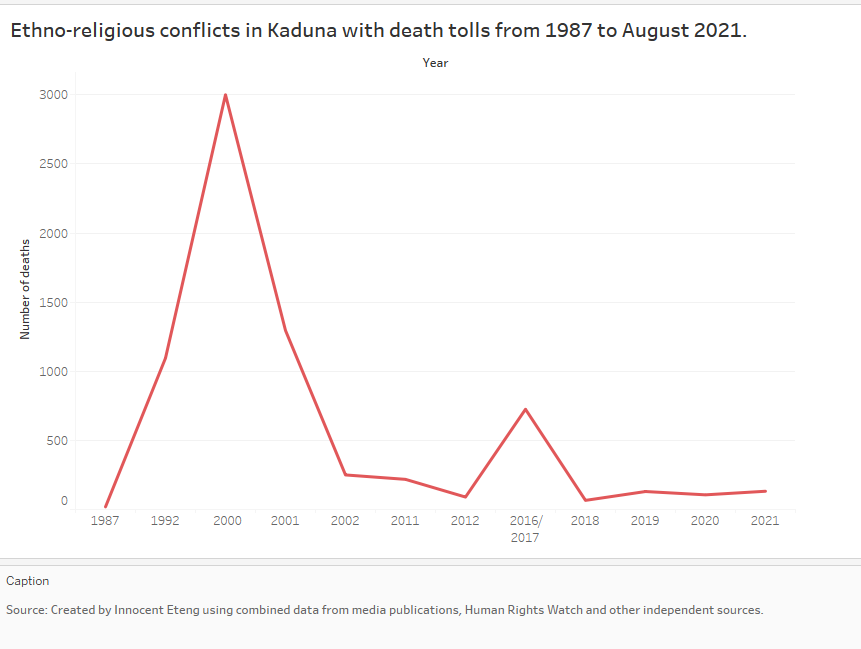

From the late 1970s, several interconnected events sprang up to puncture the peaceful coexistence of Muslims and Christians, especially in Southern Kaduna. Since then, over 20,000 people have died in different ethno-religious conflicts in Kaduna.

Sources interviewed for this report agreed on what the root causes are. The near dozen sources include Muslims and Christians in communities prone to religious violence, community leaders, leaders of interfaith nonprofits working for peace, and past and present government officials.

Several communities in eight out of the 23 LGAs in the state are most prone to violent outbreaks. These communities were identified through the help of interfaith nonprofits working for peace in the state, including the Interfaith Mediation Centre and Women Interfaith Council.

The communities include Ungwan Yero, Kwaru, Kawo, Ungwan Rimi, Ungwan Kudu and Doka in Kaduna North LGA; Kakuri, Television, Makera, Tudun Wada and Ungwan Muazu in Kaduna South LGA; Nassarawa, Tirkaniya, Sabon Tasha, Gonin Gora, Narayi, Kujama and Romi in Chikun LGA; Rigachikun and Rigasa in Igabi LGA; Kasuwa Mangani and Kajuru in Kajuru LGA; Kachia and Gumel in Kachia LGA; Zangon Kataf and Zonkwa in Zangon Kataf LGA; and Kafanchan Town in Jema’a LGA.

Meanwhile, the first identified cause of the violence was struggle over land rights from the late 1970s. That struggle, which sparked the first riots (Kasuwa Magani clash of 1980 and the Gure Mahugu Disturbance of 1984), claimed many lives and birthed an extreme ethnic consciousness that led to fault lines and divides that exist to this day.

The Christian ethnic groups often describe themselves as indigenes and owners of Southern Kaduna land while referring to their Hausa-Fulani neighbours as settlers. They claimed that they had benevolently allowed the Hausa-Fulani to settle in the land when they (Hausa-Fulani) migrated from the core northern parts of the country with their cattle and wares several centuries back.

They said the Hausa-Fulani later grew in number and started working to dominate them by forcefully taking over their lands, political structures and social and economic opportunities. They argued that the Hausa-Fulanis were also imposing Islam on them through the Zazzau Emirate Council (the current composition set up by Fulani Jihadists in 1808) which the Christian ethnic groups were politically forced to be under. They said their resistance to the domination brought them into conflict with the Hausa-Fulanis.

On their part, the Hausa-Fulani agreed that the struggle for land rights was and remains the primary driver of conflicts. But they also claimed that they settled in some parts of Southern Kaduna before the other tribes joined them.

“It [was] not [always] about religion; it is not about the tribe. It is about land,” said Abubakar Gumi, a popular Islamic scholar in Kaduna.

Because the two groups belong in two opposing religions, the clashes often take on a religious colouration as people are identified by their faiths for attacks.

Soon, political and economic discrimination and injustice by politicians started building on the ethnic and religious divide to deepen the conflict. Politicians exploited the divide, inciting and appealing for votes based on ethnic and religious sentiments, often promising to favour people of their religions and ethnic groups.

Christians interviewed for this report said political and economic injustice took roots as successive governments of Kaduna, led mainly by Hausa-Fulani, started using religious and ethnic identities as the basis for political appointments, resources allocation, infrastructural distribution, and employment into government ministries and departments.

“After that, things began to change. Differences began to erupt. That coexistence began to disrupt,” said Enock Kaura, a senior pastor with the Evangelical Church Winning All and chairman of the Christian Association of Nigeria in Kajuru LGA.

MAJOR BLODY CONFLICTS

Though clashes started in 1980 with the riot in Kasuwa Magani, the Kafanchan conflict of 1987 that killed about 19 people is known to be the genesis of religious bloodbaths in Kaduna. The Kafanchan crisis started when Muslim students at Kafanchan College of Education protested that a young Christian preacher, Abubakar Bako, blasphemed Muslims’ highly revered Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) and the Holy Quran.

Then in 1992, a disagreement over the proposed relocation of a weekly market dominated by Hausa-Fulani traders in Zangon Kataf resulted in a conflict that would later engulf most parts of the state and claim over 2000 lives.

The Sharia crisis of 2000, which began when Muslims clashed with Christians protesting the proposed extension of Sharia law to criminal matters and other hitherto unregulated matters like alcohol consumption, was yet another bloody conflict. Government records say the conflict claimed the lives of 1,295 people, but independent findings from Human Rights Watch showed that the number probably exceeded 5,000.

Then came the Miss World riot of 2002 which claimed at least 215 lives. An article published on ThisDay newspaper, a local publication, contained comments that Muslims felt Christians blasphemed Prophet Mohammed (PBUH). In protest, Muslim youths attacked and burned churches and other public and private properties, causing Christians to rise in defence of their places of worship.

There was also the post-election violence of 2011. The protest started in several northern Nigerian states when former President Goodluck Jonathan (a Christian from southern Nigeria) was declared the winner of the presidential election over current President Muhammadu Buhari (a Muslim). In volatile Kaduna, it became a clash between Christians and Muslims, resulting in the death of 180 people.

Sometimes, these conflicts happened quickly without enough early warnings to allow people run to safety or explore ways to douse the tension. Also, heavy casualties were recorded because government response to restore law and order was slow.

“When something wants to happen, you will just hear people saying, ‘They are coming; they are coming,’ and it happens,” said Mrs Paul in Ungwan Yero.

POLITICAL EFFORTS TO END CONFLICTS

The first four conflicts (1980, 1984, 1987, and 1992) happened when Nigeria was under a military dictatorship. What the state governments did then, apart from sometimes using force to end spreading riots, was to set up judicial commissions of inquiries to investigate, develop white papers and give recommendations on how best to prevent recurrence.

For example, after the 1987 Kafanchan conflict, the state government set up a committee to investigate the root causes. From its findings, a white paper containing its recommendations and government’s position was developed.

Among others, the committee recommended the creation of a new state and chiefdoms for Southern Kaduna to give them a sense of self-determination. It also urged the creation of customary courts, so Southern Kaduna people were not compelled to seek justice only at Sharia or Islamic courts. It recommended the prosecution of those who started the riot, and extension of social amenities to communities that were feeling marginalised.

Similarly, the Justice Rahila Hadea Cudjoe Commission of Inquiry was set up after the 1992 Zangon Kataf conflict. The commission submitted similar recommendations.

However, most of the recommendations were never implemented, according to current Governor Nasir el-Rufai, who set up a new committee last June to draft a white paper on the recommendations of the Justice Rahila Cudjoe Commission.

Under democratic rule, beginning from 1999, two of the biggest conflicts in Kaduna (the Sharia Riot and Miss World Riot) happened between 2000 and 2002.

To tackle the root causes of the problem, the administration of former Governor Ahmed Makarfi (1999-2007) introduced several changes. It implemented some of the recommendations of the committees on the 1987 and 1992 conflicts.

For example, his administration later watered down some clauses of the Sharia law that sparked concerns among Christians. He also created 17 new chiefdoms, with Christian chiefs heading chiefdoms in Christian-dominated areas and Muslim chiefs leading chiefdoms in Muslim-majority areas in Southern Kaduna to give each side a sense of belonging and independence. He also created customary courts for people in Southern Kaduna and balanced his political appointments, according to interviewed sources.

Makarfi also established two bureaus for Christian and Islamic matters, with a Muslim leading the bureau for Islamic affairs and a Christian heading the bureau for Christian matters. The bureaus worked with the government to deal with religious matters that could generate tension.

“Governor Makarfi got support from the Southern and Northern Kaduna people during his regime because he tried to carry all aboard. He had an open-door policy,” Muhammed Sani Isah, director of intervention at the Interfaith Mediation Center, an nonprofit in Kaduna, said.

“He could knock on your door even when you think you are a pastor… or an imam that is not known. But you will come out and see Makarfi. He would come to visit and establish ties with you. All that gave him the support from both religious and tribal groups in the state.”

Similarly, the government of Patrick Yakowa (a Christian who became governor in 2007 but died in a helicopter crash in 2010) is perceived to have been inclusive and fair to both sides in terms of appointments and working with both sides to prevent violence and keep the peace.

“They (Makarfi and Yakowa’s administrations) came as governments that were for all. In terms of appointment, they treated the state as theirs without an iota of injustice in the distribution of infrastructure. At that time, the government was for the state,” said Halliru Maraya, a popular Islamic cleric in Kaduna who was a special adviser to Yakowa on Islamic affairs.

EL-RUFAI’S GOVERNMENT SEEN AS PARTIAL

The present government of Kaduna under el-Rufai came to power in 2015. A Muslim from the Fulani ethnic group, Mr. el-Rufai has repeatedly said that his administration is fair to all. But that claim was quickly disputed by observers from the two sides who pointed to his policies they said are one-sided.

Since 2015, herders (from the Fulani tribe) have carried out multiple attacks on ethnic Southern Kaduna farming communities, with several hundreds of people killed without any perpetrator being prosecuted. For example, between May 2016 and September 2017 alone, 725 people (709 of them Christians) died in such attacks. Sometimes as many as 130 people were killed in a single attack.

The current government is alleged to have overturned and changed some of the policies put in place by the past governments, making it hard to believe el-Rufai’s claim of fair play.

For example, since 1999, it had been a tradition for aspiring Muslim governors to pick a Christian as their running mate (deputy) and potential Christian governors to pick a Muslim as running mate. The idea was to gain support from both sides and to give all sides a sense of involvement.

But after winning his first term election with a Christian deputy, during his bid for re-election in 2019, Mr el-Rufai picked a Muslim who is now his deputy. The decision was heavily criticised among Muslims and Christians working for peace.

“The issue of Muslim-Muslim ticket which heralded what we have presently… is also a contributory factor to the present lack of understanding in the state along religious lines because the non-Muslims see this as something brought to marginalise them. So, they are not happy,” said Maraya.

“Also, in the setting up of the executive council of the state, that is commissioners and the rest, you will see that a particular religion is marginalised. In terms of appointment, the present government has also erred, and it is not late for them to correct that.”

Also, in 2016, el-Rufai merged the two bureaus for Christian and Islamic matters into one and called it the Bureau of Interfaith. He appointed a Muslim as head of the bureau. Though the new bureau has a religious affairs department with two directorates on religious affairs—one for Christian matters under a Christian director and the other for Islamic affairs under a Muslim director—the directorates/their directors answer to the Director-General of the Bureau, a Muslim. Those working for peace see this as a regression to possible conflict.

“What we have now is only an (or one) interfaith directorate (bureau) headed by [a] Director-General who happens to be a Muslim. In my own opinion, I will say the government has erred in the present arrangement. It is wrong. The present government should have maintained what it inherited from the previous government,” Maraya said.

Also, in June 2018, in addition to other changes regarding the structuring of existing chiefdoms, el-Rufai changed Kauru Chiefdom (Southern Kaduna) to Kauru Emirate—the head’s nomenclature changed to ’emir’ from ‘chief’. In Christian-dominated Southern Kaduna, emirates are not popular. The name change was widely criticised and perceived as an exertion of state-supported ethnic and religious dominance.

“Some of the nomenclatures (of chiefdoms) were changed, some of the chiefs were removed, new ones appointed and some of the chiefdoms proscribed. I did not see the wisdom in that because before they were created, there were antecedents, reasons. Some troubles were happening. After creating them, so many of these troubles died. So, if you go back to that, it is like you are saying the trouble should come back,” Imam Isah said.

Efforts to get Samuel Aruwan, el-Rufai’s Commissioner for Internal Security and Home Affairs, to comment proved abortive.

When he did not reply to a text message sent to him via his personal phone number, this reporter sent an email to him with a request to comment on the allegations of bias. He replied to the email, but in his reply, he declined to comment and said that this reporter should have sought a physical interaction with him and not reach him via email. He then went on to allege bias.

“You seem to have concluded your report and just want me to respond to give credence to your forthcoming prejudice report,” he wrote.

However, Muyiwa Adekeye, el-Rufai’s Special Adviser on Media and Communication, defended some of the government’s decisions in a phone conversation. He said people should stop thinking the government should be organised along ethnic and religious lines. He queried why a Muslim-Muslim ticket has continued to raise a lot of concern in Kaduna when other states like Plateau and Benue have had Christian-Christian tickets without much dust being raised.

When this reporter pointed out to him that the peculiarity of Kaduna and its history of religious violence might be a good reason to consider balance in political arrangements, he said: “The constitution of Nigeria does not construe us as religious people or based on our ethnic identities.”

On the merging of the bureaus for interfaith into one with a Muslim Director-General, Adekeye argued that the former structure of separate bureaus for Christian and Islamic matters did not stop the Sharia conflict of 2000 and the Miss World conflict of 2002 from happening and that people should rather focus on working together for peace.

Again, when Adekeye was reminded that the two bureaus were created after the two conflicts he referenced had happened as part of efforts to prevent future violent outbreaks, he said: “What I would tell you officially is that we are not into playing ethnic and religious games. I do not think it is worthwhile sitting down to defend questions that are emanating from that (ethnic and religious) worldview.”

BOTTOM LINE AND LESSONS FROM UGANDA

In all, sources across the divide said even administrations that were perceived to have worked equitably did not do enough to discourage violence because no single perpetrator has been convicted, which is why people still resort to violence for justice.

“Up till now, nobody is serving a jail term for the eruption of those crises. No one is in prison. No one is serving a jail term to serve as a deterrent to others. Most importantly, people should be brought to book whenever they are suspected of committing any violence,” Maraya said.

Gumi said: “People don’t trust the government and the judiciary. So, if you have a problem and cannot solve it constitutionally, or you have lost your right, you resort to violence. If you have a credible government, credible institutions, all these clashes would stop.”

Meanwhile, since 1995, over a dozen interfaith nonprofits have sprung up in Kaduna with different focus areas to help religiously divided groups across Kaduna live in peace and respect each other’s religious rights.

With their presence in most violence-prone Kaduna communities through community peace observers, local partners and regular educational programmes, these nonprofits have created awareness about tolerance and coexistence, often responding to early conflict warnings.

Yet, just like religious leaders, their work is basically to persuade people to accept peace. But the power to punish and deter perpetrators lies in the hands of the government.

With all past efforts at achieving peace in Kaduna (including the 2000 Kaduna Peace Declaration that saw religious and community leaders commit to working for peace) having failed, it is time to prosecute genuinely.

Historical experience from Uganda shows that genuine prosecution, or awareness that there is a solid determination to prosecute could deter offenders and end a conflict.

For nearly 20 years, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group led by Joseph Kony, committed atrocities against villagers and communities in northern Uganda, including killing, raping, and enslaving civilians with religious undertones. All government efforts to instil peace using military might and negotiation without prosecution failed.

But in 2006, the International Criminal Court issued a warrant of arrest on Kony, the main belligerent, and his commanders following a government request that the court’s prosecutors opened investigations on crimes against humanity against specific commanders of the LRA.

The new development weakened Kony and his men, forcing them to accept a government-granted amnesty they had earlier refused with a promise to cease all hostilities and violence.

The government of Nigeria and Kaduna must do the same with all sincerity of purpose. But the residents of Kaduna State are skeptical and opine that justice may still be far off in the distance.

“Our leaders are not honest. We don’t have a real leader that carries his people along. And that is why injustice came in. And because there was injustice, the government could not call a spade a spade. And that is why many culprits were left without being convicted in court or disciplined,” said Kaura.

This story was produced with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), in partnership with Code for Africa and Ayin Network.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.