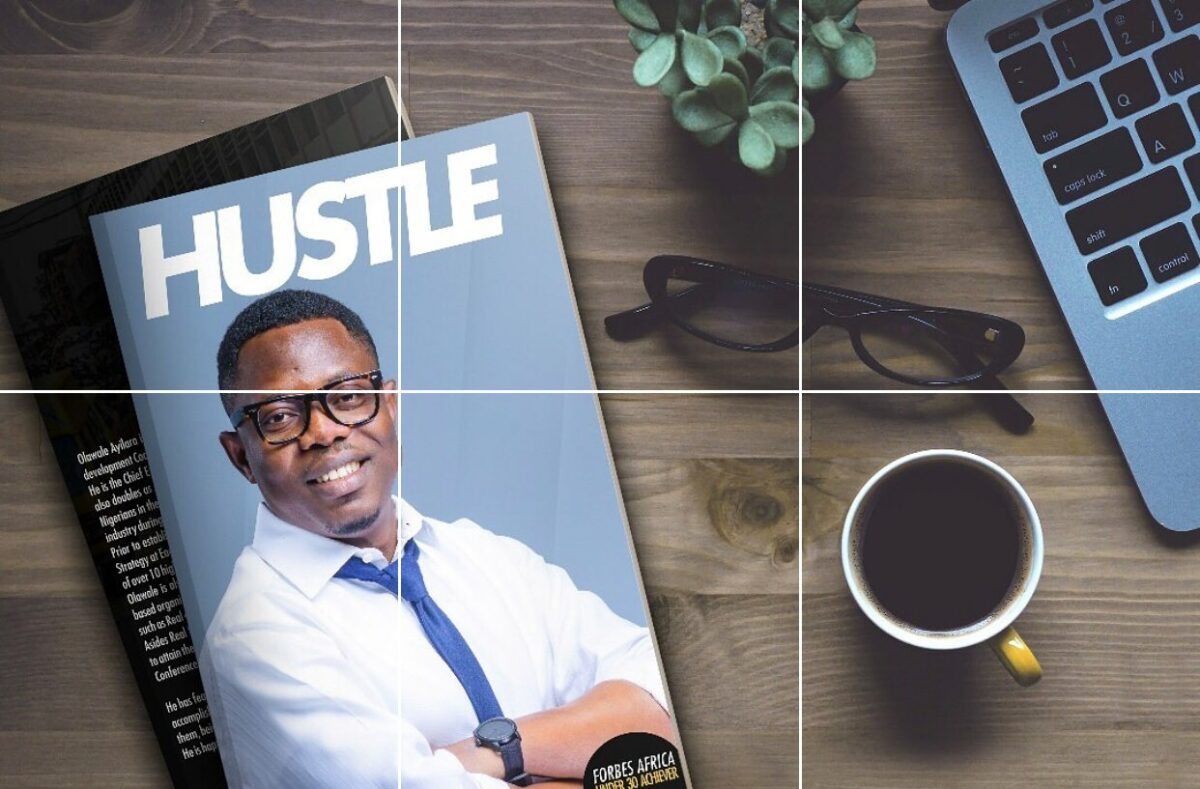

Friday April 2, 2022, was such a long time ago — it is almost a year — but not anymore. The previous day, FIJ had rung Landwey, a real estate investment company owned by overnight billionaire Olawale Ayilara, multiple times to respond to a customer’s angst at not receiving either money or property from them 21 months after paying.

After receiving N5 million and N37 million from him three weeks apart in June 2020, Landwey had promised him that his property would be ready in November. It wasn’t. Initially, they defended the delay and repeatedly asked him for patience, but by 2021, they had stopped taking his calls.

The client then approached FIJ, providing documentary evidence of a deal with Landwey, and proof of payment.

After multiple dials without connection to a contact phone number Landwey themselves had supplied on their own website, the reporter belatedly opted to leave an email. There was no reply, so, the following day, the story was published.

FIRST REACTION: AN EMISSARY FROM LANDWEY

After calling the reporter hours after the story was published, Landwey’s next reaction was to test the waters by sending an emissary to the Founder/Editor-in-Chief of FIJ to plead for the story to be taken down. The reply, of course, was that this was impossible.

FIJ was set up to help people like this secure social justice. If Landwey had collected N42 million from someone without delivering, then they had to do something. The emissary was worried about the bad press for the real estate business, but he was assured thus: “FIJ is not after anyone’s business. If Landwey refunds him or delivers his property to him, we will write that positive story too. The so-called ‘negative story’ will be eventually cancelled out by the positive follow-up.”

It ended there. Or so we thought.

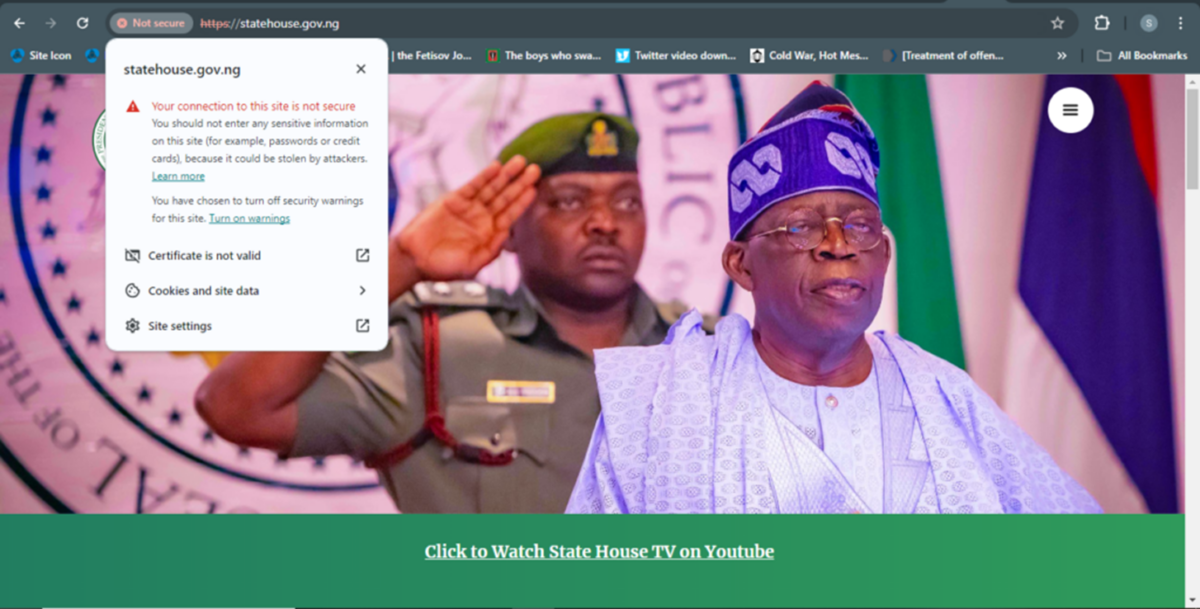

PULLED DOWN BY DIGITAL OCEAN

On Thursday, February 23, just two days to the 2023 presidential election, FIJ’s website, fij.ng, became inactive. We reached out to our web consultancy, only to be told they had missed two emails from DigitalOcean accusing us of copyright infringements. As we would find out, the problem was not that the emails were missed; DigitalOcean did not conduct any investigation, which a basic tool like the Wayback Machine would have done for them. DigitalOcean did not even ask us to prove our ownership of the story. They had just one instruction: take the story down!

The first email, dated February 16 and signed by the Security Operations Centre of DigitalOcean, said FIJ’s April 2022 story on Landwey’s failure to fulfill its obligations to a client “was the subject of a notification of claimed copyright infringement pursuant to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)”.

“DigitalOcean takes seriously the DMCA notices it receives and expects its customers to do the same,” it said. “Accordingly, no later than 3 days from today, you must certify in writing that you have removed or disabled access to the material identified in the attached DCMA notice. If we do not hear from you within 3 days, we may disable access to the Droplet without further notice.”

The second email from DigitalOcean, dated February 22, gave us an extra 24 hours to pull the story down. When we didn’t, DigitalOcean simply pulled our entire website down!

WHAT, REALLY, IS THE DCMA?

The US Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on October 28, 1998. The legislation implements two 1996 World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) treaties – the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty – and is divided into five titles, one of which is the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act, which creates limitations on the liability of online service providers for copyright infringement when engaging in certain types of activities. In this specific case, the idea is that websites who copy others’ works do not get away with it, as their website host is compelled to disable access to the offensive piece.

However, in order to protect against the possibility of erroneous or fraudulent notifications, certain safeguards are built into Section 512 of the Act, thus:

Subsection (g)(1) gives the subscriber the opportunity to respond to the notice and takedown by filing a counter notification.

In order to qualify for the protection against liability for taking down

material, the service provider must promptly notify the subscriber that it has removed or disabled access to the material. If the subscriber serves a counter notification complying with statutory requirements, including a statement under penalty of perjury that the material was removed or disabled through mistake or misidentification, then unless the copyright owner files an action seeking a court order against the subscriber, the service provider must put the material back up within 10 to 14 business days after receiving the counter notification. Penalties are provided for knowing material misrepresentations in either a notice or a counter notice. Any person who knowingly materially misrepresents that material is infringing, or that it was removed or blocked through mistake or misidentification, is liable for any resulting damages (including costs and attorneys’ fees) incurred by the alleged infringer, the copyright owner or its licensee, or the service provider.

Going by the above, DigitalOcean did not have a right under the law to disable access to FIJ’s website; they only had the powers to disable access to the specific story in question. Again, DigitalOcean were mandated by the law to restore our story after our explanation, unless they received superior notice from the complainant. They haven’t received any such notice – at least they didn’t share any with FIJ – and they have foreclosed any opportunity for restoration by writing us to say they would no longer host our website.

HOW WALE AYILARA’S LANDWEY DID IT

Someone claiming to be ‘Luis Felipe Colina’, all the way from Venezuela, swore under penalty of perjury that he had detected infringements of his copyright interests by FIJ.

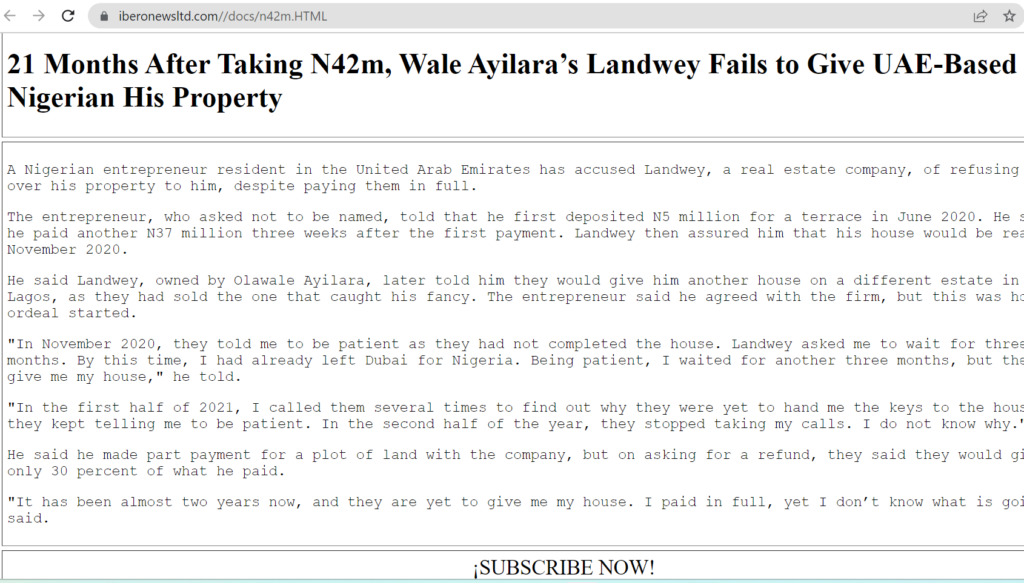

He claimed that FIJ’s piece of April 2, 2022, titled ’21 Months After Taking N42m, Wale Ayilara’s Landwey Fails to Give UAE-Based Nigerian His Property’, was orginally his. Colina claimed to have first published the piece in a private newsletter he circulated on April 1.

“I have reasonable good faith belief that use of the material in the manner complained of in the report below is not authorized by myself, my agents, or the law,” he wrote.

“Therefore, this letter is an official notification to effect removal of the detected infringement listed in the report below. The report below specifies the exact location of the infringement.

“I hereby request that you immediately remove or block access to the

infringing material, as specified under Section 512(c) of the Digital

Millennium Copyright Act (the “Act”). Please insure the user refrains from using or sharing with others the unauthorized materials in the future.”

But all that was a ruse. FIJ is in possession of evidence showing the email is the handiwork of an international PR firm employed by Ayilara to cleanse his digital footprints of negative comments.

THE MULTIPLE HOLES

First, a Vezenuelan individual who isn’t a journalist or real estate aficionado has no business reporting a Nigerian real estate company that took N42 million from a client without delivering the property. There’s no way any such Venezuelan could have reported that story.

Next, Colina’s newsletter is clearly cooked up. There’s no other piece on that newsletter, and its ‘subscribe’ icon is unresponsive. It is impossible for anyone to subscribe to getting Colina’s past or future newsletters — because they simply do not exist.

Three, https://iberonewsltd.com, the website on which the newsletter was supposedly hosted, does not exist. Any attempt to reach that website will only yield the following: “404. Not Found. The resource requested could not be found on this server!” How could DigitalOcean have believed a non-existent website had been plagiarised by an exiting investigative reporting outlet?

DIGITAL OCEAN, MASTERS OF THE CON GAME

It’s not like DigitalOcean did not know Colina was lying. An ‘American multinational technology company and cloud service provider’ surely knows how to establish the first of two claimants to have published a piece. Ask on the streets and you will surely run into someone who will refer you to the Wayback Machine if you want to resolve any such dispute.

So why did DigitalOcean play along? Because this is not their first time! ‘THE GRAVEDIGGERS ELIMINALIA, a piece by a consortium of journalists for ‘Forbidden Stories‘, a collaborative journalism network devoted to pursuing the work of threatened, jailed, or killed journalists around the world, details how DigitalOcean once pulled down the work of Daniel Sánchez, a Mexican investigative journalist.

In 2018, Sánchez, a journalist at Página 66, a small investigative news outlet in Mexico’s southern Campeche state, had published an investigation into the bad track record of a video surveillance company, Interconecta, contracted by the state’s governor. Sifting through financial audit records, Sánchez discovered that the company, a subsidiary of the tech multinational Grupo Altavista, had been linked to cases of corruption and tax fraud.

Two years later, a supposed local marketing expert calling himself Humberto Herrera Rincón Gallardo emailed Sánchez to claim the article infringed upon a European data law called GDPR and asked him to remove references to Grupo Altavista and its founder Ricardo Orrantia. The email was signed by the ‘Compliance Department’ of the European Union. Sánchez, perplexed, consulted Artículo 19, a press freedom organization, for advice; he was told not to remove the piece.

But a month later, Gallardo was back. This time, he filed a claim with DigitalOcean, Pagina 66’s US-based hosting provider, alleging that Sánchez had copied his content illegally. As proof, Gallardo linked to a third-party site that had published a replica of Sánchez’s piece, but with a falsified earlier publish date and fake author: Humberto Herrera Rincón Gallardo.

This time, the strategy worked. DigitalOcean ordered Sánchez to remove his article from Página 66’s site, or it would go black. He appealed to DigitalOcean but was unsuccessful. Finally, fearing he would lose his readership, and his livelihood as a journalist, he capitulated and removed the piece.

Clearly, this is all familiar territory for DigitalOcean.

In FIJ’s case, DigitalOcean did not only block FIJ’s website, it rejected all our defences of being the original copyright owner. It then went ahead to blacklist FIJ.

“Due to violations of our Terms of Service, we have blocklisted your domain fij.ng. You can no longer host this domain (including its contents and/or subdomains) on our network,” it wrote back after a string of emails from FIJ.

“Please have a look at the previous tickets we have sent you in regards to Intellectual Property infringements. This domain has been added to our Blocklist for repeated copyright infringement and circumvention of the DMCA.

“We are providing you with 48 hours to remove this domain and its contents from our network. After this point, we will be disabling networking on the associated droplet if the domain and/or content is still live.

“Please note that moving the domain (or its contents) to a new Droplet is not sufficient – the domain must be removed from our network.”

NEXT STEPS FOR FIJ

FIJ’s legal team are currently studying the development in its full scale, and will come up with recommendations within the next 48 hours.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.