For eight weeks, investigative journalist Ibrahim Adeyemi traced the deaths, destruction and disappearances from the military invasion of Konshisha, Benue State, in April 2021. He names dozens of innocent citizens massacred by soldiers on a revenge mission and reveals their faces, after the Nigerian Army denied the killings and challenged the public to present evidence.

Ngufan Terkimbi gave birth to a baby girl three days ago. Today, the baby would save her life. The 28-year-old was running off-the-cuff when a bullet targeted at her hit the skull of the newly born. Covered with blood, she moaned in pain, but the gunfire would not stop.

A military aircraft hovered above the town. Soldiers jumped down from their vehicles in combat fashion, firing heavy artillery to the south and the east. Bonta, a town in the Konshinsha area of Benue State, became a scene of tears, blood, and smoke.

“I dropped her in the bush, ran for my life and returned to bury her,” Terkimbi recalls, amid tears. ”We had to run for our lives when the military commander ordered his men to ‘Shoot! Prrrrrr!’”

BACK WITH A VENGEANCE

The killing spree started after 11 soldiers and a commander were slaughtered by ‘Bonta Boys’, a contingent of local militants in the town, for allegedly supporting and supplying arms to their rival group. Afterward, hundreds of soldiers, armed to the teeth, barged into the community, aggressively shooting in all directions, according to multiple witnesses.

Villages in Bonta bore scars of the military attacks. Several houses and farm stores were burnt to dust. Walls were marked with bullet holes amidst caved-in roofs. In Gbinde market, for example, only a few shops were standing amid the rubble. During the invasion, residents say, vultures fed on bodies of men, women and children lying on the ground for days.

Gbinde Market, Koshinsha Local Government, Benue.

However, the Nigerian Army denied killing the innocent villagers. The narrative provided by the authorities was that the troops were deployed to the town to fish out the bandits that murdered their colleagues and seized their ammunition. They admitted to killing only 10 bandits and challenged anyone to produce evidence of their mass-killing of innocent civilians.

“The Defence Headquarters wishes to put it on record that apart from these initial 10 bandits, there are no other civilian casualties recorded in any part of Konshisha till date,” a statement by the military reads.

“We, therefore, challenge anybody from Konshisha to present to the public the 200, 70, or 30 dead bodies of innocent persons, male, female, or children killed by troops in Konshisha. There was never a massacre as being touted by some mischief-makers.”

THE BLOODBATH IN BONTA

Isaac Kajo was farming when the soldiers pillaged Gulya, a village near Bonta. Seeing the hovering helicopter, Isaac held his cutlass firmly, ready to defend himself.

His phone rang. The caller informed him that a neighbour was dying of gunshots from the troops. He dashed out of his farm to save a life, but a rocket hit him in the neck. He groaned in the pool of his blood, eyewitnesses say, and died.

“Had he listened to me, he would still be alive today,” says 72-year-old Mbayeghkaa Kajo, Isaac’s father. “I warned him not to go out. I told him not to leave the farm. And now he’s no more.”

Mbayeghkaa said his son’s death was a punishment from God for an offense he was yet to identify. Isaac, the only son taking care of him at his old age, was no more. Everybody, especially his father, felt his absence in the household. He was the major source of survival for them before death took him away.

Felicia Kajo, wife of late Isaac Kajo, holding the portrait of her husband.

Father, wife, children … The family Isaac left in terrible condition

Felicia Kajo, his wife, stared at her husband’s picture sparingly. The portrait of Isaac carrying a bottle of beer reminded her of how hard-working he was and how much he liked to have fun as much he loved to take care of his family.

His five children are now out of school. His abducted children are also left to suffer. At 2 pm, the family was deliberating on what to prepare for breakfast. The septuagenarian grandfather could neither farm nor do any business.

“If my husband was alive, we wouldn’t worry about how to feed,” Felicia says, her voice breaking in rapid succession. “He was the glory of the family.”

DEARTH AND DISEASES

Comfort Sule, 50, was sick. When she coughed, blood gushed out of her nose; she breathed slowly and heavily. There was an ache behind her eyes, she says, and tightness in her chest. Sitting in front of her house in Gungul, another village near Bonta, she stood up to welcome this visiting reporter. When she spoke, silence punctuated her lines as though words were forced out of her mouth.

Comfort Sule looking pale and sick after the death of her husband.

The killer soldiers destroying Bonta were in Gungul. It was a hide-or-die race. Everyone was running. Boniface Sule, her husband, was having a short nap. The roar of the military helicopter woke him up. As he rushed out of the room to see what was happening, a rocket fired from above hit him. He died on the spot. Sule was buried in the backyard of the house.

“Living without my husband is difficult,” Comfort says in Tiv Language. “It’s hard to feed and survive. He used to do everything for me. As old as I am, he treated me like a new bride. He never allowed me to do any stressful work.”

There were marks all over her body, save for her grieving face and shivering hands. Asked about the nature of her sickness, she says she has no idea. She can’t afford a hospital bill, so she takes herbs for the undiagnosed ailment.

“My children are still very young and I have to take care of them,” she says. “There’s no one to help. I am only looking up to God to heal me.”

DEATH ON THE PROWL

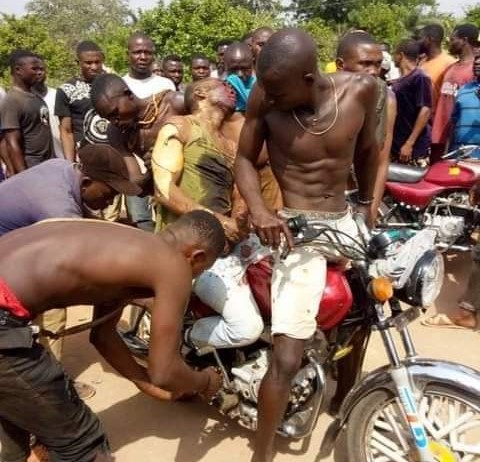

In Mbawar, a hamlet in Gungul, Kpenlangan Chado, 30, was trying to dodge a military airstrike. He pulled up on his motorcycle, throttled its engine to full steam and sped off. Sadly, the motorcycle suddenly tumbled, his forehead smashed on the rubble along the road. Fallen and soaked in blood, Kpenlangan let out a loud painful screech before some low dying moan.

Kpenlangan Chado died terribly, says his brother

On the evening this fatal accident happened, Nguuma Abragi’s motorcycle caught fire from the bullets shot at him. Left alone amid the sporadic shootings of the Army, the 14-year-old picked up the key to his father’s motorcycle and ran away. The motorcycle burst into flames when the military airstrike hit it. The fire engulfed the fleeing boy. He did not survive.

Christopher Udoh, 47, a member of the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW), died trying to escape. He lost control while running on a motorcycle to avoid gunshots from the soldiers. His chest hit the ground as he fell from the motorcycle. Christopher first passed out, according to eye-witnesses, and later passed away.

Magdarine Tswe, 50, wept bitterly when she told the story of her son’s death. Agunna Tswe, her son, was the only prop in her distress. But he had been killed by the invading soldiers.

Magdarine Tswe tells the story of how her son, Agunna Tswe, died

Agunna, who was sent to the farm to harvest some produce, was killed by the military. Amid the violence ruining their community, the 22-year-old jumped on his bike, running for his life. He had not got home when a bullet struck him in the eye.

“I was told the bullet came from heaven and killed him,” Magdarine says. “They brought his body to me and I saw that my son was dead.”

A FAMILY PERISHED BY THE ARMY

Samuel Yenge, 50, was agitated. His wife and seven children were still missing four months after the military invaded the village. When the soldiers started shooting, Yenge says, everyone ran for his life. The terror in the land met him on the farm and his wife and children at home.

“By the time I came back. My house was on fire,” he says. “There was no one at home. I could not find my wife and children.”

If Yenge had a mystical power, he says, he would invoke it on the soldiers that invaded his home. He had lost two children to terminal illnesses before the soldiers’ invasion. Now, his seven other children: Joseph, Terkimbir, Maria, Selumum, Sengohol, Aondosoo and Kwasedoo, were nowhere to be found.

Terhamba Kughur, a neighbour who had joined Yengi in search of his family, suggested that they might have been ambushed during the military invasion.

“We’ve searched everywhere,” Kughur says in Tiv Language. “We’ve even reported to the police and the vigilantes. Our fear is that the soldiers could have ambushed them in the bush while running.”

Terhamba Kughur, the man whose means of livelihood was ruined by the Army

Kughur showing some scars of bullet wounds on his body

Kughur himself still bore scars of bullet wounds on his body. His livelihood was ruined, he says. His barber’s shop was demolished and his home razed down.

Yenge became homeless in his own home. He would pass nights in his neighbours’ homes — something he would ordinarily not do before the military attack.

“Could they have all perished in the bush, ambushed or struck by the rockets fired by the Army?” Yenge wonders.

CHILDREN MISSING AMID CONFLICT

On April 7, when the violence was first unleashed on the people of Bonta, posts from eyewitnesses filled the Twitter page of this reporter. FIJ received on-the-ground videos and pictures of restless parents crying helplessly in search of their missing children. Eyewitnesses said hundreds of children were nowhere to be found after the Army raided the community.

“I was in the kitchen and saw a helicopter shooting; everybody was running. I ran away, leaving my children behind. Up till now, I cannot see my two children,” a woman said in one of the videos, shedding tears.

In another short video, a man narrated how dozens of children on the playing ground had run in different directions and how they had not set eyes on any of them since then.

FIJ also received pictures showing stranded children and women displaced by the soldiers lying on the bare floor in terrible conditions. We would later find out that only a few children were reunited with their families. Uncounted numbers of children did not return; they were either perished by the Army or banished to God-knows-where.

Aondofa Kernum, 7, ran for his life when a bullet pierced the window of his house in Bonta. He had since been missing. His 78-year-old father says his other five children were missing on the day of the attack but came back “after some days”. However, Aondofa would not return.

A child missing in the conflict

“I’ve searched everywhere but can’t find him,” Kernum says. “There is no place I’ve not been to. I also begged people to help me look for him but he’s nowhere to be found.”

Eight-year-old Ngodoo Oban and nine-year-old Sesugh Doohiin suddenly disappeared in Tse-Kyado, a small village in Bonta. Rockets fired by the Army had put the villagers in disarray. Several children disappeared in the process. Most of them returned to their families but Ngodoo and Sesugh never did.

Terpase Kyado, 5, vanished amid the military bombardment. Tergu Kyado, his father, did not know whether his son was dead or alive. The last day he saw him was on April 8, during the military artillery raid. The killing spree forced the whole village to embark on an everyone-for-himself race. Many children went off the mark, including Terpase and Tergu’s neighbour’s child, Terkende Numbe, a three-year-old.

“I have a feeling my son has been killed,” says Nenge Numbe, Terkende’s father. “My spirit is telling me that he is no more.”

EVEN INFANTS WERE NOT SPARED

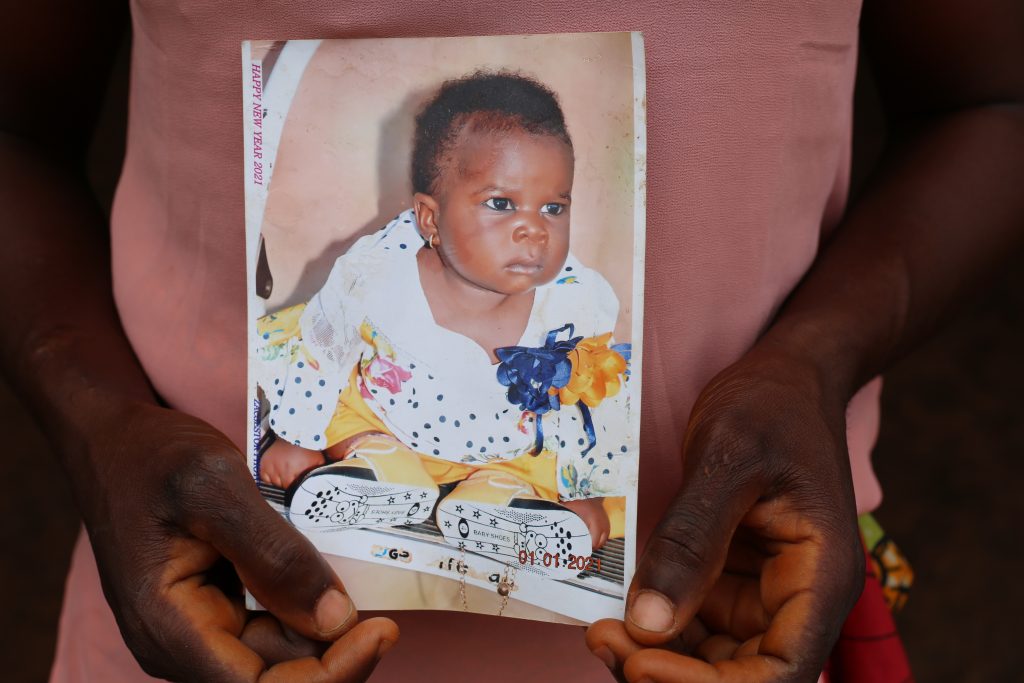

Nine-months-old Anita Biem, killed by the Army

Soniah Biem, 20, was taking refuge in the bush with her nine-month-old daughter, Anita Biem. It was evening and Soniah was breastfeeding her crying daughter in their hideout. Amid the explosive sounds of guns and the roar of the military jet, the toddler suddenly lost breath and died.

“My daughter’s death makes me feel sad every time I remember,” Soniah says, shedding tears. “I think I didn’t protect her enough while we were hiding from the soldiers. Her death is painful.”

Ikyurav Terlunmun, 35, says his son died terribly. He fled his house hearing sounds of gunshots from the Army and left his son and wife behind. When he returned, his son, Terdee Terlunmun, 4, was soaked in his own blood.

“I was in the house. I didn’t know anything was happening. So, when I heard gunshots, I ran,” Ikyurav recalls, his red eyes filled with grief. “When I came back and saw him dead, I was sad. He’s my third child. I loved him. I didn’t wish him death.”

Children perished by the Army

Ushahemba Atondo, 32, found the decaying body of his son three days after he was shot by the Army. Lutor Atondo, the two-year-old son, had been declared missing on the day the fatal cocktail opened in Bonta. Ushahemba had fled with his three other children. He left Lutor behind, believing the soldiers would not be so brutal to kill an infant. He was wrong.

“To my surprise, we found him dead in the bush, after searching everywhere for three days,” says Ushahemba, telling chilling tales of how his son died. “We had no other choice than to bury him in my compound there.”

TWO FETUSES MISCARRIED ON THE STREET

Terngu Maakaven, 20, lost her twin fetuses amid the invasion. It was a month to her date of delivery and Terngu was preparing to go for her antenatal at the Bonta clinic when the soldiers invaded, spraying bullets indiscriminately in the community.

The pregnant woman scampered for safety, dashing into the nearest bush. She suddenly slumped and hit her chest and stomach on the hard surface of the floor. A few hours later, Kuha Maakaven, her husband, found her bleeding in the bush and took her to the nearest hospital. He found out that his wife had lost the pregnancy amid the hanky-panky.

The eight-month fetus was buried in Kuha’s compound. According to him, his wife had been mentally disturbed since the incident.

“I had to take her to her mother’s house because we’re still mourning,” he says.

ELDERLY PERSONS WERE ALSO KILLED

Gabriel Saambagbe telling the tragic story of his father

Adeu Saambagbe, 61, decided to remain calm under the baobab tree in front of his house while others ran to avoid being gruesomely killed. As the soldiers fired bullets in his direction, Adeu maintained his position, as if he did not fear death. His son, Gabriel Saambagbe, was hiding in the bush, waiting for his father to join him. The next thing he heard, he says, was a repeated gunshot fired into their compound at Tsom-Ayom village.

Believing that the soldiers had left the area, Gabriel came out and saw his father’s lifeless body lying helplessly on the floor. He couldn’t believe his father had been killed. Moving closer to get proof of life, he saw him covered with blood.

“We were here together under this tree when we were told that the soldiers were coming for us,” Gabriel recalls. “I ran into the bush to hide but he refused to go with me. When I came back thinking the soldiers had gone. I saw that he had been shot in the leg and the head. The soldiers came back again and started chasing me with guns. But I managed to escape.”

Ngoshior Asongu, 61, was killed by the Army.

Hon Tenti, 90, killed by the Army

Steven Asongu, 29, said he left his mother, Ngoshior Asongu, when the soldiers invaded their home. When he returned, his 70-year-old mother had gone missing. He combed the entire village in search of the mother of 10 children but couldn’t find anyone that looked like her.

Ngoshior did not return. Her son said he believed her mother could have been killed somewhere in the bush by the Army.

“We’ve searched everywhere in this village, yet we can’t find her,” he said. “She’s still missing up till now. That means there is something wrong. The soldiers could have killed her and thrown her away in the bush.”

Ninety-year-old Hon Tenti died running for his life when the “agents of death” appeared, shooting in Mbator village. The old man, who had been suffering from a chest ache, started vomiting blood while running. But his children could not immediately wait to take him to the hospital. Everyone was looking for an escape route.

“When we came back, we found him dead,” says Bashiki Tenti, his son. “Before the soldiers came, he was having chest pain. So, his body system could not withstand the pressure. He died.”

NOTES ON GRIEF [1]: THE MASSACRE AND THE COVER-UP

When the Nigerian Army denied massacring innocent villagers in Konshina and challenged anyone to come with evidence, what it forgot was that the truth cannot be hidden forever. In what seems like a deliberate blackout on the reportage of the mass-killing, dozens of soldiers laid siege to the invaded communities for weeks, trying to clean up their mess before it would be exposed.

A community journalist who tried to document the plight of citizens killed by the soldiers got the beating of his life. His phones and gadgets were seized. He was almost killed.

“They must not see anybody with an Android phone around. You couldn’t even move closer to the community,” the journalist told FIJ, sharing his experience. “When I tried to enter the village as a journalist, I was harassed, embarrassed and beaten to stupor.”

However, an investigation by FIJ, spanning four months of on-the-ground reporting, intelligence gathering and interviews with multiple sources, including families of victims, witnesses, hospital officials, and the Army, revealed the Nigerian military plotted the massacre of innocent citizens of Benue as a way of avenging the death of their murdered soldiers.

| S/N | NAMES OF VILLAGERS MASSACRED BY NIGERIAN SOLDIERS | HOW THE VICTIMS DIED DURING THE MILITARY INVASION | AGE |

| 1 | Isaac Terugu Yajo | Shot by the military airstrike | 35 |

| 2 | Agune Joseph | Shot by the military airstrike | 25 |

| 3 | Kpenhayen Chado | Shot by the military airstrike | 35 |

| 4 | Mrs Mbaideve Abo | The shock from the military invasion | 45 |

| 5 | Lit Biem Ansha Selimon | Died of malnutrition where there is no refuge | 9 months |

| 6 | Nonjolor Stephen Shagee | Shock from gun sound | 65 |

| 7 | Mr. Senda Terungwa | Shot by soldiers | 48 |

| 8 | Yaakwahy Ihyandegu | Heart attack | 90 |

| 9 | Boiface Sule | Heart attack | |

| 10 | Dooyum Tyokirghir | Collapsed and died hearing sounds of gunshots | 15 |

| 11 | Saagbe Adeu | Heart attack | 65 |

| 12 | Denis Linm | Collapsed and died hearing sounds of gunshots | 63 |

| 13 | Vitalis Ikpuughul | Heart attack | 65 |

| 14 | Ngufan Terkunsor (miss dain) | Died of a heart attack | 38 |

| 15 | Vangeryina Geera | Died of a heart attack | 65 |

| 16 | Lorina Yasunye | Shot by soldiers | 30 |

| 17 | Gbamwuan Tseku | Shot by soldiers | 37 |

| 18 | Detsa Avalu | Shot by soldiers | 22 |

| 19 | Tyavmbi Amula | Shot by soldiers | 40 |

| 20 | Tyegusa Igbana | Shot by soldiers | 42 |

| 21 | Michael Yyolaha | Shot by soldiers | 31 |

| 22 | Iorhuma Tyodear | Sustained gun injury and died later | 26 |

| 23 | Iorbec Poor | Heart attack | 58 |

| 24 | Kukase Esther Jen | Heart attack | 82 |

| 25 | Ashi Tyoakula | Heart attack | 72 |

| 26 | Member Tersoo | Heart attack | 47 |

| 27 | Luther Ush | Killed by soldiers | 2 |

| 28 | Ikyokaw Terrder | Killed by soldiers | 4 |

| 29 | Nenge Tervenda | Killed by soldiers | 3 |

| 30 | Keyernum Terfa | Killed by soldiers | 2 |

| 31 | Aomlonge Sanmmapi | Killed by soldiers | 3 |

| 32 | Terlumun Martha (Tse-number) | Killed by soldiers | 22 |

| 33 | Mimi Ngodoo (Tse-Tembe) | killed by soldiers | 6 |

| 34 | Ikyuraw Doowuse (Tse-number) | killed by soldiers | 23 |

| 35 | Kyado Terpase (Tse-lagada) | killed by soldiers | 5 |

| 36 | Doolin Sesugh (TSe-number) | Missing | 9 |

| 37 | Orbam Ngodoo (Tse-layada) | Missing | 8 |

| 38 | Tartaue Tseneeke (Mbaashini) | Missing | 35 |

| 39 | Igbayima Udugh (Mbakunda) | Killed by soldiers | 40 |

| 40 | Hon Tenti (Tse-jemba) | Heart attack | 100 |

| 41 | Ahon Ngiuan (Tse-number) | Heart attack | 35 |

| 42 | Ordungurge Dyako | Heart attack | 50 |

| 43 | Kertor Mindi | Gunshots from the soldiers | 18 |

| 44 | Kumawuese Tarkidegh (Tse-Ajoko) | Heart attack | 18 |

| 45 | Ukor Nyitar (Tse-Jembe) | Heart attack | 100 |

| 46 | Nanem Terlumuu (Tse-Jemb) | Heart attack | 6 |

| 47 | Terngu Makaven (Tse-Kyado) | Miscarriage | |

| 48 | Terhile Akuse | Gunshot | 35 |

| 49 | Nguuma Aberaki | Shot | 12 |

| 50 | Terseu Shom | Missing | 15 |

| 51 | Asongu Ngoshior | Missing | 70 |

NOTES ON GRIEF [2]: THE HUMANS AND THE NUMBERS

Obituaries of innocent people killed by soldiers littered the walls of the villages. During the visit to Bonta, different gatherings were organised at one place or another to mourn the sudden departure of young and old persons. This reporter compiled and verified names, photos and videos of villagers wasted during the Army’s inhumanity to man.

FIJ independently established that over 50 persons were killed during the attacks. About 34percent of the massacred villagers were children and adolescents of ages between 0 and 17. About 42percent were youths of ages 18-49, while about 24percent were elderly persons. Many of these casualties either died of military airstrikes or direct gunshots from the soldiers. Very few persons died of a heart attack due to the Army’s fatal violence.

However, FIJ’s months of investigation have shed light on the deadly violation of human rights perpetrated by the Army at a time Nigeria was under international scrutiny over the mass killings of #EndSARS protesters.

In its execution, the bloodshed is similar to the 2001 Zaki-Biem massacre. The soldiers took revenge on the unarmed people in what ranks among the cruelest use of force in the history of Nigeria. The mass killing can also be compared with the 1999 Odi massacre, the 2016 Zaria mass killing, and the 2021 Lekki and Obigbo bloodsheds.

NOTES ON GRIEF [3]: BURIED WITH THEIR PICTURES

Bonta, by all accounts, was the worst hit with dug graves dotting the expanse of the town. Dozens of lives were lost almost without a trace, making it easy for the Army to deny the killings. Many families and relatives of victims of the massacre said their houses were burnt and that they lost the pictures of their loved ones to the war.

In some parts of Bonta, pictures of the dead are buried with them — an old tradition forbids villagers from keeping such pictures in their homes — according to residents. As such, many of the villagers did not keep the photos of their kinsmen killed by the Army during the invasion.

“It’s a culture in some parts of Bonta,” says Jembe Emmanuel, a community leader. “When people die, it is expected that you bury their pictures with them. That is why many people may not be able to produce pictures of the people killed.”

However, the pictures for this story were obtained from those who managed to have one or two photos of the deceased, either hard copies or those on mobile phones. The names and pictures of victims of the massacre were verified by this reporter after weeks of combing about 20 villages of the town.

NO COMMENT FROM THE ARMY

On several occasions before and after concluding this investigation, FIJ placed several calls to Oyema Nnwachukwu, the Nigerian Army’s spokesman, to ask him questions on the findings in this report, but he did not answer any. He also did not respond to the text messages sent to his phone. But Muhammad Yerima, former spokesperson of the Army, who released the statement challenging “anyone present evidence of the mass-killings of innocent civilians, warned the reporter to focus his life on reporting constructive stories.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.