FIJ’s OPEYEMI LAWAL took a boat trip from CMS, Lagos, to Maria a Tokpa, Port Novo, to explore the security checks put in place to curtail the flow of migrants or smugglers who might use the sea route since the land borders are closed.

In the shadowed hall of the National Inland Waterways Authority (NIWA) on June 20, I needed to convince myself I knew what I was doing. This wasn’t an accidental trip, but thoughts of the over 100 people who died in the Kwara boat accident kept filtering into my head.

The news had shaken my confidence, and just as I slouched my handbag over my shoulder that morning, a colleague reminded me I couldn’t swim before waving me off reluctantly to face the scariest adventure of my life.

I got into the NIWA hall at 10:01 am. A long brown counter held cardboard tags of destinations: ‘Apapa’, ‘Badagry’, and ‘Port Novo’. At the counter, I met a man who asked where I was going.

“Port Novo,” I said. “How much is it?”

“Seven thousand naira,” he responded.

“That’s a lot of money.”

“Fuel don cost.”

READ ALSO: REPORTER’S DIARY: Has Tinubu Opened Land Borders? I Went to Idi-Iroko to Find Out

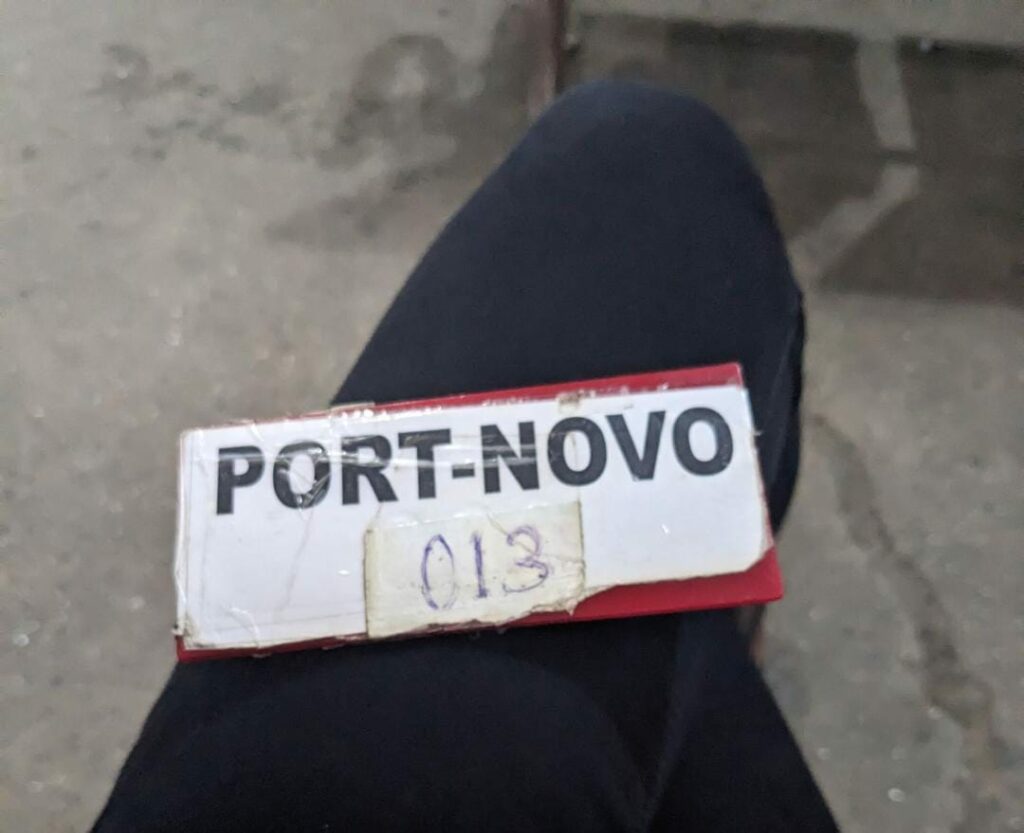

I counted seven N1000 notes and handed them to him in exchange for a plastic red tag with ‘Port Novo’ and number ‘013’ written on it.

An overzealous agbero was quick to lead me to one of the joined seats. The silver paint was fading, and the rust of the iron used to build the seats was becoming visible.

“Madam, sit here,’ he said.

I sat beside Isaac, an 18-year-old, who told me that the pilots were waiting for five more passengers to fill up our boat.

The traffic of people in the large waiting area didn’t cease for a minute. More people, mostly women, arrived with large baskets of different kinds of seafood balanced on their heads. The hall, aside from being a place to wait for your boat or ferry, was a small market. Different businesses thrived there, from cooked food to snacks, point of sale (POS) businesses, foodstuff, drugs, etc., just about anything you want.

Isaac tried to prepare me for what to expect. Unlike me, he was a regular, but nothing prepared him for the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA)’s search into his luggage. I understood that this was a major port, and it was not unusual for the anti-drug agency to be stationed there. But Isaac would have none of it when a fair-skinned officer approached him and took us into an office cut off from the hall. The only attractive item in the grey office was the gold-coated nameplate which read “Adekunkle Bolanle Nurat”.

The NDLEA officer peered into Isaac’s bag. He searched it all and found nothing incriminating, and then he allowed us to go. But Isaac didn’t find the exercise pleasant.

“That was harassment,” he mumbled to me on our way out.

“No, he was just doing his job,” I responded.

“But it has never happened before. No one has ever searched me here, and I use this route often,” he said again.

“I know, but there is always a first time to everything.”

A FAILED ENGINE

The five passengers arrived and the same overzealous agbero ushered us to the dock where we found more seafood traders displaying their wares. Two men worked on the boat with a navy blue exterior and a faded dark blue interior, the one that had ‘Only God’ written on it. I noticed that the life jacket I was handed also had the same inscription. And truly, only God would save us from the twists to follow.

Two other men who worked with the boat owner haggled with passengers over the worth of their bags. I would later learn that the pilots charge passengers based on the size of their luggage.

Isaac’s was told his medium-size Ghana-must-go bag would go for N3,000. The battle that followed was intense, but he insisted on N500. “I am a regular on this route. If you try to show you have money, they will rip you off,” he told me.

The men were soon to arrange the loads beneath our seats and the front part of the boat. Shortly, 18 of us, including two pilots, were set to sail, and our boat ground into the Nigerian Navy water at 11:06 am.

The speed of the boat as it ground over rocks and splashed water on our faces didn’t prepare us for an abrupt stop on the sea 11 minutes into our journey. The boat swayed lightly when the tide was low, but swerved left or right when the current was high. The pilots got to work immediately, and just as I was mumbling a prayer of protection and safety, the engine roared back to life.

We cruised through industrial parts of Lagos, which spanned to the right, and smaller islands to the left, but just as civilisation began to disappear, our engine went off again with a loud gasp, and the boat stopped.

All we had were our lives, our prayers and our hopes. Nigeria had recorded a number of boat accidents lately, and only a few passengers on the boat could swim. I wasn’t one of them, and it didn’t look like anyone could survive in the black inky water for long. The pilots paddled us to somewhere around Tincan Island. There, we found out that the pilots had made us sail on a speedboat with a faulty carburetor.

“This man does this every time. His boat is never in good shape,” a hugely built passenger said. “If I had known this was his boat, I wouldn’t have boarded.”

“Why did I choose to travel on a Tuesday?” Cynthia, who would later become my tour guide, asked. “How would you put so many people on the water here in the name of fixing your boat? People just conduct businesses however they like in this part of the world.”

A HOP FOR FREE PASSAGE

| S/N | WHO | WHERE & WHEN | EXPERIENCE |

| 1. | Navy and Army | Arakumo – 1:10 pm | Not checked. |

| 2. | Military | Badagry General Hospital – 1:20 pm | Not checked. |

| 3. | Customs | 1:24 pm | Not checked. |

| 4. | NDLEA | Close to Gbaji bridge – 1:26 pm | Not checked. |

| 5. | NDLEA | Akere – 1:43 pm | Not checked. |

| 6. | Immigration | Akere – 1:43 pm | Not checked. |

| 7. | Immigration | 1:47 pm | The only place our travel documents were demanded. |

| 8. | Checkpoint | Tofin – 2:03 pm | Not checked. |

| 9. | Checkpoint | 2:09 pm | Not checked. |

| 10. | Checkpoint | 2:10 pm | Not checked. |

| 11. | Checkpoint | 2:12 pm | Not checked. |

| 12. | Nigerian Customs Western Marine | Yekemeh – 2:14 pm | Not checked. |

In the course of our 3 hours, 32 minutes trip to the Republic of Benin, we came across several security checks, but one of our pilots jumped into officers’ boats with some money to save us the trouble.

Isaac had told me that even if I was carrying anything illegal or didn’t have my travel documents, I wouldn’t have to worry because the security officials would be too busy checking what the pilot dropped for them. As we travelled further, we passed tiny islands with palm trees swaying around their banks. Most of the houses were far away, and for miles and miles, we were only surrounded by tall leafy trees, seaweeds and the sky.

We passed through Ikare, Beshi, Iyagbe, Ilashe, Badagry Creek, Okun Ajaga, Irewe, Orufo, Ibode, Agomu, Agonu, Maroko, Tafi, Ojogun, Wuru, Ajido and smaller communities.

Our first checkpoint was at Arakumo. There, we saw naval and army officers. Our pilots rowed our boat close to theirs, and just as Isaac predicted, one of them hopped into their grey boat to grease their palm. After a few conversations, we continued our trip.

We didn’t have little to entertain us on the trip. The screeches from birds and the lull of the sea filled our ears; while boats rowing into the sea, a bundle of plastic waste and lone political flag of the All Progressive Congress (APC) billowing in the sky in Agomu filled our eyes.

Many passengers dozed under the scorching sun. On days like this, one would miss the luxury of the yellow buses in Lagos. Everyone became alert when our boat dipped violently somewhere around the Badagry General Hospital.

We realised that we were approaching a second checkpoint. Here, we met a military checkpoint with a soldier in a stilt house. He waved us off after another hop. This was 1:20 pm.

The third checkpoint was only four minutes away. We met an officer of the Nigerian Customs Services, who also greeted us cheerfully. Two minutes further, we accosted two NDLEA officers whose purses also grew richer with our pilot’s quick hops into their boat.

After this, we crossed the Gbaji bridge and docked at Gbaji-Yeke, where we had our first and only stopover.

We left Gbaji-Yeke and ran into the NDLEA and immigration officers at Akere. Our pilot did the needful, and we continued our trip.

Soon, we entered the Ogun waterways. There was a sharp contrast between the two states in tidiness. Dozens of seaweeds and hyacinths floated on the ocean. Fallen trees also contributed to the green cluster.

The seaweeds led us into the major stumbling block of our journey: immigration checks. We were caught unaware when our pilot rowed close to the immigration boat. We thought it was business as usual until a stoic immigration officer asked us to present our travel documents. Our pilot hopped, but it was not enough.

“Where are your passports or Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) ID cards?” The officer asked.

The question was surprising, as none of the officers at the six check points we had passed stopped to interact with passengers.

“Let me see your passports or ECOWAS ID cards,” the officer said again.

A lot of “I-am-not-with-it” and “It-is-at-home” came from the passengers. Those who had a passport were quick to present it to bail themselves.

Those who didn’t have it were made to alight into the officers’ boat. The officer threatened to send them back to Lagos, but the travellers soon returned to narrate how they bribed their way through. The guy who sat next to me didn’t have an international passport or ECOWAS ID card. He credited the officer’s failure to check him to God’s grace.

The search left most of the passengers unsettled and disgruntled. Some blamed the officer for being overzealous, while others boasted about how they could enter and leave the country without travel documents.

At Tofin, the free pass continued. We met a checkpoint with a lone Nigerian flag. From there, we were ordered to raise both hands as we approached two more checkpoints within minutes. We moved further and got to another checkpoint before the last Nigerian checkpoint at Yemekeh. The bill board read, “Nigerian customs western Marine – Yekemeh station.” Our pilot hopped for the last time on Nigerian water, and we entered Port Novo. This was 2:14 pm.

MARIA A TOKPA, PORT NOVO

Some five minutes and we were in the Republic of Benin. The waterways shared similarity with the Ogun, Nigeria waterways. It had tens of floating seaweeds and hyacinths.

By 2:23 pm, we reached the first Benin check point, where money changers advertised their rates to us. Nobody checked us to know if we were coming into the country with anything illegal. A few minutes away from there, and we were at Maria a Tokpa, Port Novo, our boat’s destination.

With stiff limbs and sun-scorched bodies, we alighted from the boat to be accosted by young boys who pushed their wares into our faces. They advertised MTN sim cards with Benin Republic numbers to us.

“Aunty, buy MTN. It is everywhere you go,” one said.

Another one pushed past him and pushed his bundle of SIM cards into my face. “Buy Benin number,” he said in a mixture of Nigerian and Benin Yoruba.

As we entered a dusty cream building, we were searched by the Beninese immigration. Almost every turn with the Beninese officers was brief, and we were soon out of the hall to explore the city.

FEWER SECURITY CHECKS

The following morning, I was set to return to Lagos. I was in high spirits, having explored a part of the city the previous night, but the weather had a different mood.

Through the help of a Nigerian who speaks both the local Fongbe and French, I got a taxi to take me back to Port Novo. I had difficulty interacting with most of the locals as we spoke different languages. The driver, who likely acted on what my Nigerian friend had told him, took me to a different port, and I failed in my attempts to explain that I was heading to a different destination.

I would later find out that there are two ports in Port Novo. The first place (where I alighted the previous day) was governed by strict immigration laws, while the place the driver took me to on Wednesday morning, Wetan, was easy.

Wale, a Nigerian-Beninose I met at the jetty explained that anyone willing to escape custom checks would patronise the Wetan Jetty.

“This port is beneficial to people with extra luggage because over there, you will have to deal with customs, and then your load will be weighed for payment. Here, you don’t pay by weight. All you do is get into the boat and move,” Wale said.

If I prayed the previous day, I prayed harder on my trip back to Lagos. A drizzle that had started on my way to the jetty became torrents after I arrived the port at 8:32 am.

Our pilot, a slim young man who appeared to be in his late twenties, tried to assuage our fears. After trying to court the weather without luck, we set sail in the rain at 10:45 am.

The rain slapped our faces and forced all nine of us, including the two pilots, to bend our heads. The sky broke lose and the sea rose to meet it. As the rain poured, the two pilots spread a big polythene over everyone to keep us dry and reduce how much rain got into the boat. The thought of excess water getting into the boat made me pray harder.

Despite the rain, the return trip was faster. We were at the first Republic of Benin checkpoint by 11:02 am. A few women and more luggage joined the boat and we were off again.

While we passed through Akere, Akhovo, Doforo and got to Gbaji, we didn’t see any checkpoint. But as soon as we left Gbaji, there was a customs checkpoint with a good that had recently been seized.

Our pilot didn’t have to hop; the humility he wore on his face gave him a free pass. He had the demeanour of a young man who liked to avoid trouble.

We didn’t run into any trouble until 12:31 pm when we got to the Maroko checkpoint. There, a customs officer demanded that one of us open her bag for a search.

“Oga, there is nothing there,” she tried to argue.

“You go open am make I see,” he said. “You go open am.”

But just as she was about to obey his command, he changed his mind and waved us off.

The rain made my return trip less eventful. All we had was the symphony of music from the rain and the sea as we huddled under the white polythene.

I arrived CMS, Lagos, at 2 pm with frozen fingers and cold bones, and with the realisation that if my pilot could hop well, I could leave Nigeria with no travel documents and some contraband and not end up in jail.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.