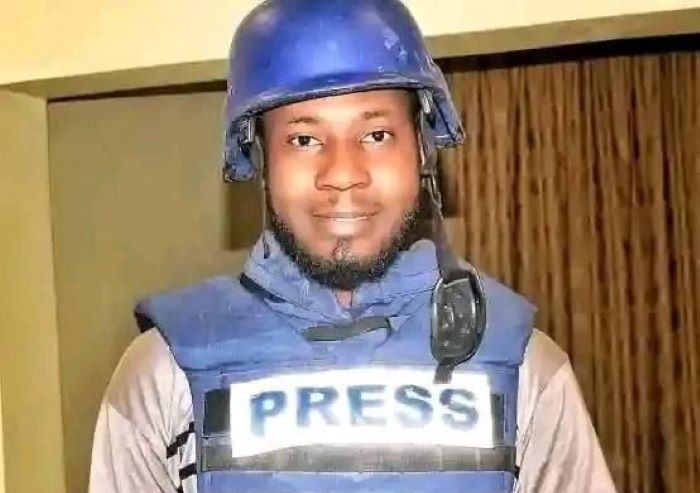

On March 7, terrorists rode into LEA School in Kuriga, Kaduna State, abducted 138 persons. FIJ’s DANIEL OJUKWU visited Kuriga, pored through documents, investigated the abduction and learned the government had at least a five-year headstart to forestall the attack.

Photo Credit: Daniel Ojukwu/FIJ, March 24, 2024

On motorcycles, unmasked men with guns, machetes and other weapons rode boldly into LEA School, Kuriga, Chikun LGA of Kaduna State. It was the morning of March 7, 2024, and townsmen were preparing to sleep when the first shots went off.

The night before, these townsmen had performed their ritual of patrolling the community with hunting guns to scare terrorists away. This they did every night in the past three years because there were no uniformed men in Kuriga to protect them. By morning, they were tired and convinced the terrorists would not strike without the cover of darkness, so they went to bed.

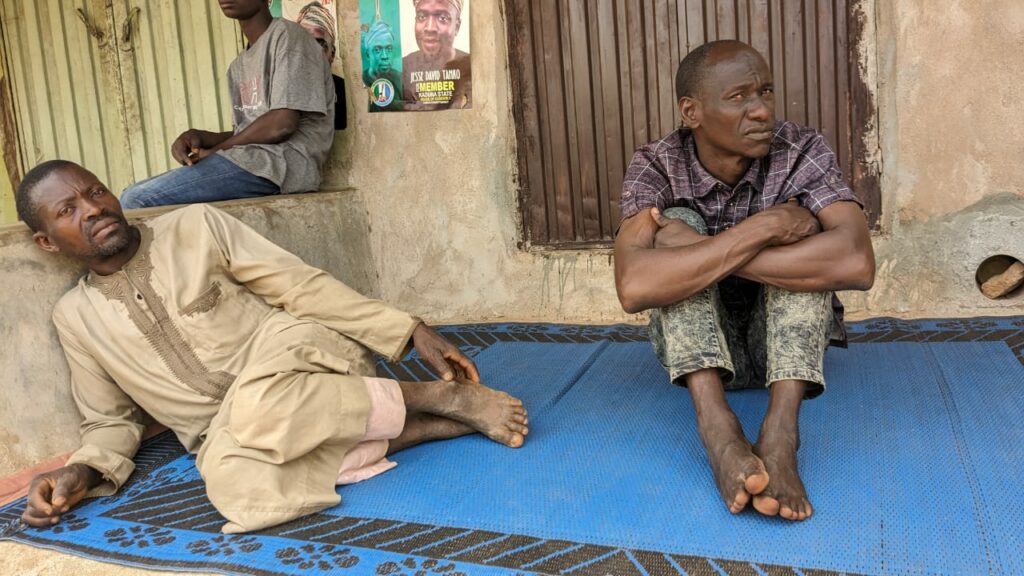

From some 200 meters away, Jibril Abdullahi and Dahiru Abdulkarim could hear shots. Abdullahi’s son and Abdulkarim’s daughter were in school that morning when both men heard familiar gunfire coming from where the 13-year-olds should have been learning. They panicked.

Inside the school, the children also panicked when they saw the men who would soon be their captors. As danger approached with no sense of urgency from the main entry point, these children scurried to exit through the back. The school was fenceless, so they were defenceless against the ambush that lay in wait where they headed.

“We raced to the school and watched the terrorists march into the distance with our children,” Abdulkarim told FIJ. “Our children ran to the open field behind the school, but more men were waiting to capture them there. We could not do anything because there were many of them, and we lacked the facilities to chase. All we could do was watch.”

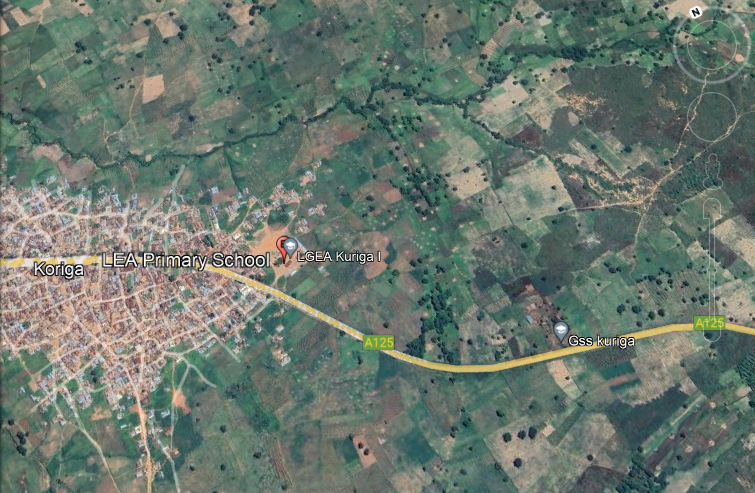

Source: Google Earth Pro

Map modified to show routes through which terrorists gained entry and exited with captives

GIS mapping: Daniel Ojukwu/FIJ

While Abdulkarim recounted the events of that day, Abdullahi wore a long face and stared at nothing in particular, as though lost in thought. Earlier in the day, the government announced the return of his son and 136 others, but there was neither excitement nor relief in his demeanour.

It was the same blankness that plastered across the faces of several residents of the area whom FIJ met with on that day. People went about their lives like nothing happened, as though it were just another Sunday. Abduction for ransom was commonplace here.

Nothing characterised how much levity the community expressed more than their handling of the missing persons’ roster. When the abduction took place, parents whose children were taken were brought together to document their names. What security and community sources then got was a document with 287 names, but FIJ would later learn that some of the names were duplicated. Only after their release did 119 parents come together to document the names of their 137 children.

As other sources would later corroborate, Abdullahi revealed the community had been under siege for many years, and the government knew about it but abandoned them to defend themselves as terrorists rummaged through to either abduct or kill them at will.

Photo Credit: Daniel Ojukwu/FIJ

COMMONNESS OF KURIGA’S TERROR

Why did the country take so much interest in the Kuriga school attack? Why was a small community on the outskirts of town receiving international media attention all of a sudden after years of sustained violence? The residents wanted to know. Had the abduction not mirrored the 2014 incident in Chibok, Borno State, would the government have helped?

Aminu Saleh (not real name) is a member of the state civil service, and this status stops him from speaking officially to the press. However, when FIJ was in the community of his birth, he had no kind words for the government. “They took it seriously because children were involved,” he said. “We all saw this coming and told them about it, but they did not care. They left us to die.”

The events of March 7 should leave a scar on Saleh, but while he refused to visit the school since the abduction, his decision was not born of fear or trauma. “I watched it all happen. They rode past me as they went to the school,” Saleh relayed to FIJ. “It was not the first time we would see terrorists in our midsts, but it was surprising to see them during the day. Some of us grabbed our hunting guns and shot in their direction, but we were powerless.

“It is possible one of the terrorists was injured during the shootout, but they sped off with the children and we could not tell what became of this terrorist.”

Like other men, Saleh had gone out on patrol the night before. He was tired by morning, but he said even if he weren’t, it would have been impossible to stop the terrorists. “When we patrol, we use dane guns and shrapnel as bullets. The aim is not to kill our oppressors but to scare them off,” he said.

Why wouldn’t Saleh and his neighbours shoot to kill those who want to kill them? “If we kill one of them, the rest may bring mayhem upon us and raze the community down,” he said. “What we do is just shoot to make loud noises and force them into a retreat. This tactic would have failed on that morning.”

Since 2011, Kuriga has been facing occasional terror attacks. These attacks have been difficult to foil because the closest police station to the community is in Udawa, 24 kilometres away from the LEA school, meaning it would take at least 40 minutes for the police to come to their rescue — if they managed to hear about it. The community had no cell reception, so no one could make phone calls to anyone they wanted to send messages to. To communicate, they would journey to a cyber cafe, pay for WiFi access and send texts or make online calls to anyone on social media. Attacks usually start and end in shorter times than they would need.

“They took it seriously because children were involved. We all saw this coming and told them about it, but they did not care. They left us to die.”

Aminu Saleh

On the other side of the highway is Birnin Gwari LGA, a community with a long history of terror attacks. Kuriga was trapped, and its only option was to defend itself since the government wouldn’t help. For context, the community used to have a police outpost, but this outpost was removed in 2021. Sources say the police feared it would be the first target for terrorists if they returned with force, and because it lacked the manpower to contain attacks, the police took it out. Spokespersons for the police refused to comment on this.

FIJ called Muhammed Jalige, but he refused to comment, saying there was a new PRO. Jalige was the spokesman for the police in 2021. When FIJ called Mansir Hassan, the current spokesman, he promised to get back to this reporter, but he declined subsequent calls.

YEARS AGO, COMMUNITY SAW SCHOOL ATTACK COMING

Photo Credit: Daniel Ojukwu/FIJ

Kuriga bleeds, but it has been doing so for years.

To tell the story of men who no longer walk among the living, one often relies on those who saw them. In Nigeria, since the Boko Haram sect gained national notoriety in 2009, there has been no shortage of fatal attacks in the country’s northwest.

There are often names, figures and statistical data sets for lives claimed by terrorists within locations and periods. But Boko Haram is not the only terror sect bedevilling the region. Several bandit groups have sprung up to compete for dominance and thrive in unprotected areas. One of these groups has robbed Kuriga LEA School of at least five teachers since 2017.

Abubakar Isah used to teach Agricultural Science while serving as the principal of LEA Junior Secondary School. Now he is dead, but his death could have been avoided. His government failed him. FIJ learned that 137 children were abducted in March 2024, but there were 138 captives. He was the only staff taken and the only captive to not make it back alive.

The secondary school he spent years leading sits some distance away from the community’s residential area and used to operate until 2021, when the primary and secondary schools merged.

The reason both schools merged, Saleh explained, was because the community feared the distant secondary school was susceptible to attacks. They saw it coming.

Source: Google Earth Pro. GIS mapping: Daniel Ojukwu/FIJ

Data from Google Earth Pro shows the Kuriga LEA Primary School sitting on the edge of the community’s residential area, and the secondary school (Government Secondary School Kuriga) some 750 meters away from the primary school, isolated and swallowed by vegetation. Its isolation led the community to close it down in 2021.

This secondary school used to have two principals; Isah for the junior secondary school and Eedris Abu-Sufyan for the senior secondary school. Bunyaminu Mu’azu served as vice principal for both senior and junior secondary schools.

While it remains unclear the circumstances surrounding Isah’s death, his chances of living a long and fulfilling life were slim even before the abduction.

READ MORE: BREAKING: Abducted Kaduna Children ‘Released’

Findings by FIJ confirmed staff of the school were targeted by terrorists for seven years, and no fewer than five of them were killed. Two months before Isah’s death, terrorists broke into Abu-Sufyan’s house, scattered bullets all over his house and sent the community into panic mode. Sources familiar with the incident said they did not have to see what was going on to know death was in the offing.

When the noise died down and the assailants were long gone, Abu Sufyan was dead. This was the fourth LEA staff to be killed since 2017. He was the latest casualty in LEA’s long history of stolen lives and cut dreams. “In 2017, terrorists killed Bola AbdulAziz, a biology teacher in the school,” Saleh told FIJ. “That same year, they killed Sani Abubakar, an English teacher. Four years later, they killed Saifullah Zakari Ya’u, a chemistry teacher, before the killing of Abu-Sufyan in January this year.”

FIJ obtained pictures and details of the teachers killed in Kuriga in seven years. This data has been documented in the chart below:

EVIDENCE OF NEGLECT

How does a community without cell reception communicate to the government and the outside world that it needs interventions? Through letters, a cyber cafe and intelligence reports.

When Isah was taken with the abducted children, he gave the phone number of Jibril Gwadabe Kuriga to the bandits. Jibril Gwadabe was a Kuriga resident who was in Kaduna town when the kidnapping occurred. While he was away, his 12-year-old daughter was marching into Zamfara forests with her principal and peers. He would not see her for another 17 days.

“The terrorists told Jibril they wanted N1 billion, but they did not want our money,” sources told FIJ. “They wanted it from the government because the children were ‘government’s children’, according to them.”

This communication helped get the nation’s attention to the crisis in the area and sparked nationwide calls for government intervention. Previous attempts to alert the government failed.

FIJ sighted an intelligence report prepared by the Department of State Services (DSS) in 2019 calling for the immediate intervention of the state government, federal government and security agencies to provide on-the-ground security for Kuriga residents as they were facing increased undocumented attacks.

The source of this document would prefer not to be named, as the government could target them. They also revealed the document was prepared after Kuriga suffered an attack in April 2019. Nasir El-Rufai took the oath of office for a second term as state governor, and Samuel Aruwan became the state’s head of internal security, privy to intelligence reports like this one.

FIJ mapped reported cases of attacks in that period and found some. On April 19, 2019, a Daily Post headline read, “Armed bandits sack inhabitants of Kaduna village.”

Source: Daily Post

According to this report, terrorists wrote to the community on April 18, 2019, and warned them to leave. They struck the following day, abducting five women and men. Scared survivors fled to Birnin-Gwari to live as internally displaced persons.

The Birnin-Gwari Vanguard for Security and Good Governance issued a statement saying, “We urge all security and intelligence personnel to be on alert and salvage this ugly situation.”

Two years later, the police outpost disappeared.

Before the 2019 attack, there was an April 5, 2018 attack in the same community. Nasir el-Rufai, then state governor, sent food items to the community four days later, and according to a statement by the Kaduna State Emergency Management Agency (KADSEMA), he assured “the people of his continuous effort to provide security for all in the state”.

After this assurance, more incidents were documented in 2018 here, here and here.

Following a June 5, 2018 attack, a resident spoke to newsmen, saying, “We were attacked by armed bandits just one week after some people in uniform came around 1.00 am in search of arms. We suspect foul play in this attack.

“The attacks, like many others around the Birnin-Gwari axis, continued without any attempts by the security personnel to repel them. However, the vigilantes from neighbouring Udawa and Birnin-Gwari succeeded in repelling it.”

With no police or military presence in the community, one may imagine the governor would keep his promise of improving security there at the time, given the frequency of attacks, but no.

Checks by FIJ revealed that only once did El-Rufai mention Kuriga in his official statement, from 2015 when he assumed office to 2023 when he handed over to Uba Sani.

On November 20, 2022, El-Rufai issued a statement that Aruwan signed. This statement was a security update that listed several areas where the army was carrying out airstrikes as part of Operation Whirl Punch (OPWP). He mentions Kuriga as one of the areas the army patrolled in that period.

There were no other mentions of the area in any official statements until the March 7 abduction.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM

A DSS operative who spoke with FIJ but refused to be named said the service had discovered the activities of three main terrorists competing for dominance in the area.

These three are known as Yellow Janbros, Dogo Gide and Dankarami. A report stating the government paid ransom to the abductors of the schoolchildren quoted a source who said Yellow Janbros and Dogo Gide participated in the abduction.

On March 25, a day after the children’s release, the DSS operative told FIJ that the DSS had learned that the three terrorists were terrorising Niger, Zamfara and Kaduna State and that the Kuriga abduction incident had spurred Dankarami to rally his boys around Kajari area to plan a weightier attack to draw national attention.

“We just got the intel today,” the DSS source told FIJ. “We passed it along to the military, and they may do a clearance operation in the Kajari area.” Dankarami is suspected to be linked with the March 2022 Abuja-Kaduna train attack.

Now, we have a sense of the people who executed the attack and how the government got the students back, but you should remember Saleh did say the same government watched them die in the past.

“We all saw this coming and told them about it, but they did not care. They left us to die,” Saleh said.

When FIJ did not get a response from the police, this reporter called Major General Onyema Nwachukwu, spokesman for the Nigerian Army.

Nwachukwu said he visited the Kuriga school after the abduction and was surprised to find no security presence. He said he found that the school was dilapidated and had no fences or protection of any sort. FIJ has compiled pictures of the school taken during our reporter’s visit. They can be accessed here.

When FIJ asked if the military had seen the 2019 security report and why there was no military formation in the area to deal with bandits, he defended the military.

“Military formations cannot be everywhere,” Nwachukwu said. “When we are invited to defeat bandits in an overrun area, we do clearance operations and fight the terrorists to a standstill before handing over to civil security agencies.

“It is the job of these civil security agencies to set up formations in these reclaimed territories and ensure the terrorists don’t return while we retreat into the forest. The primary duty of the military is the protection of the nation’s territorial integrity.”

FIJ asked if the military had passed this complaint along to the police and other agencies, and he replied saying, “We have had several discussions. I am not mentioning the name of any security agency, but if you understand Nigeria’s security structure, you would know civil security groups from local to state to federal levels that should provide internal security.”

The Kaduna State Government has a Kaduna Vigilante Service (KADVIS) that supports the efforts of police and other security agencies. This service had no presence in Kuriga. So there was no police, no vigilante service, and no other form of security, despite a 2019 warning. FIJ earlier found that KADVIS was understaffed and underfunded.

Moreso, the only time el-Rufai ever issued an official statement mentioning Kuriga was when the military ran an operation in the area in 2022. Despite this operation, the state and federal governments still failed to beef up security.

Kunle Adebajo, a journalist who has authored several conflict and security reports, shared his experience with FIJ. He said in a telephone interview that he had been to communities in Zamfara and other states where there were abandoned police posts and checkpoints, like the Kuriga reality.

“There are communities ravaged by bandits and terrorists where you would not find police or military presence at all,” he said. “Nigeria does not have enough security agents to cover the country’s land mass, and some policemen are working as security personnel for VIPs and private individuals.”

Adebajo referred to Aminu Masari’s 2022 complaints of inadequate security in Katsina State as a pointer to how poor security is in the region. Masari, the Katsina Governor, had claimed that about 30 policemen were protecting around 100 villages in the state, alluding to a manpower problem.

FIJ called Muyiwa Adejobi, Force Public Relations Officer, but he did not take our calls. As of press time, he had not responded to our message. Aruwan, the head of Kaduna State internal security under el-Rufai, also did not take our calls or respond to our messages.

On April 10, FIJ again called Jalige. He answered the call this time, but after hearing our questions, he said he was going to attend Eid-el-Fitr celebrations and would call back, but as of press time, he had not done so. FIJ called el-Rufai’s known phone numbers on the same day, but the former governor did not take our calls.

In 2022, FIJ found a document detailing a list of terrorists in the state. This document contains their locations and phone numbers, but when the newspaper approached Aruwan with this information that the state government should be in possession of, he dismissed it and never acknowledged receiving it. FIJ also sent this document to Jalige.

Kayode Egbetokun, the Inspector-General of Police, recently mobilised policemen to defend Kuriga after the release of the abductees, and all seems to be well, but Saleh does not quite agree.

“We still come out at night to patrol the community, but we would soon get used to the police,” he told FIJ. “We are not the only community facing insecurity here. I wonder what the government is doing about other communities that have been complaining, too.”

*Names changed to protect sources’ identities.

This story was produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.