Reading FIJ makes you realise how quickly time passes, and working here only makes it even more so. It is hard to believe that a year has passed since I welcomed you into our third year with the top 10 stories from the previous year, but I am excited to share with you another 10, carefully chosen from the more than 2000 stories that have been added to our list in the last 365 days.

In an effort to strengthen democracy and promote society, our reporters journeyed to uncover dark secrets and expose corporate and governmental wrongdoing from the United Kingdom to Benin Republic and the rugged corners of Nigeria.

Here are 10 of our biggest:

Following 19 months of research and observation, FIJ’s founder and editor-in-chief, ‘Fisayo Soyombo, finally purchased a baby from Arrows of God, a well-known Lagos orphanage run by Rev. Col. LTC D. C. Ogo (rtd), a former military woman and preacher. Rev. Ogo had been trading babies for cash, and ‘Fisayo only needed to pay N2 million naira to get a beautiful girl. That baby turns one in another two weeks!

Here’s the story in part:

My ‘wife’ and I gave Arrows of God a few weeks before resuming the calls. They were seamless this time. If we called, Rev. Ogo answered. If she missed our call, she rang back, even if it sometimes took days. The year ended without any noteworthy development. We talked in January and again in February. By then, the conversations had become routine: be patient, I haven’t forgotten you, just keep praying, God will do it soon. And so on.

March was stalemated; and by April, I had started to wonder if my cover had been blown. Had they found me out? Did they call one of the fake numbers on the letters and found it unreachable? Did they call another, and then another, all unreachable, and then began to suspect me? Had they discovered my real name, that I actually wasn’t Paul Runsewe?

On Friday June 2, 2023, my ‘wife’ woke up to 11 missed calls from a strange number: This was followed by two more calls from the designated Arrows of God phone number. Our baby was ready. Until this point, nobody from Arrows of God had given us the slightest hint of how much we were buying the baby for. Just before they kick-started the conversation on money, they sent us a picture of the baby — something in the realm of proof of life sent by ransom-seeking kidnappers to families of their captives.

In 2016, a family brought their 10-year-old son to the Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) Industrial Area Clinic in Rumuobiakani, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, for a “simple, straightforward 30-minute” appendicitis surgery; however, they returned him nearly dead. When ‘Fisayo Soyombo visited Chizaram in a UK hospital in 2023, he was bedridden and in the same miserable state he had been in for seven years. The hospital was fully to blame, but they refused to accept responsibility.

“For me — and this is even where my pain started from — Chinazam went in for the surgery at about 2pm, but from then until 7pm, nobody, I repeat nobody, said anything to us,” laments Stella [Chizaram’s mother]. “For five hours, we were just standing, sitting, walking up and down. If any door opened, we ran there, and someone told us ‘Oh, they’re just about to finish’. And the hours went by.”

Stella and Emeka were still sitting in the visitors’ lobby when the anaesthetist, Dr. Dafe Akpoduado, exited the theatre to converse with another doctor on the phone. Unbeknownst to the anaesthetist, the Okolis were within earshot. “For the rest of my life,” says Stella, “I can never forget what I heard.”

“I no no wetin happen o,” she quoted the anaesthetist as saying in pidgin, his hands akimbo. “Na water water full everywhere o, the brain, the kidney, the this the that, na water water, I no know o, I no know wetin con happen.”

Stella stepped out to confront him, prompting the doctor to defend himself: “I was not there o; I was not part of the team; he was just giving me a handover note.”

Emeka walked across the corridor towards the theatre, asking to see his son. The surgeon, Dr. Alexander Dimoko, met him by the theatre door and told him: “Chinazam had a drug reaction but is okay now.” Stella was next to go in. Thinking her boy was dead, she “wept bitterly” until the doctor told her “no; he’s still alive”.

“What I saw on that day, may nobody ever go through this — even people who say they have enemies,” she says. “Oh Jesus! May nobody ever go through this period.”

Shortly after, Chinazam was wheeled out on some life support systems into the Intensive Care Unit as the parents looked on, while the doctors kept whispering to one another.

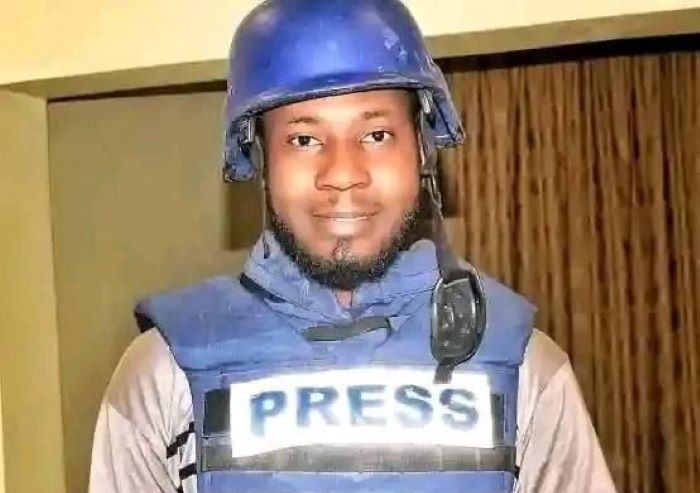

When a stray elephant died in 2022, barely 24 hours after capture by the University of Ibadan (UI), a lot of Nigerians wanted to know why. It was to find answers that Damilola Ayeni, FIJ’s editor, travelled to different parts of Nigeria and then to Benin Republic. But he almost never returned, as he was arrested and charged with terrorism.

I arrived at Pendjari National Park around 5 pm the following Thursday exhausted, but only for a group of rangers to order me to go back at the gate. Just like that, after four hours travelling from one side of the sea to another. From Lagos to Porto Novo to Cotonou and then Parakou, I had travelled for about 14 hours, nine of it on a night bus from Benin south to north. I had travelled another six hours from Parakou to Tanguietta after sleeping a night in a hotel. I had passed Tchachou; I had passed Tcharou and about a hundred villages. I had passed Copargo where the road leads to Burkina Faso, and Natinghou dominated by Hausa from Niger. I had passed a tiny road between split rocks, with bends that could put anyone in heaven or hell; all this only to be told to “go back” without explanations. To where would I return? I had planned to spend the night in one of the national park cottages. Good hotels are as rare as hen’s teeth even in Parakou, the headquarters of the whole of Borgou District, much less here. I had told these rangers I was a tourist and journalist from Nigeria. I put on my phone camera and spoke again: is this not a tourist centre?

“You’re recording me!” the leader of the rangers exclaimed and then ordered my arrest. I was handcuffed immediately and led into the park. When we got to an isolated spot, they took off my shoes and searched my bag. They found only my laptop, clothes and a book. They had taken my professional ID card, ECOWAS passport and phones. They then put me in the innermost room of one of the park cottages and locked it up. It was the first of my eight cells in Benin. First, I thought it was an arrest and that more proof that I was a journalist would get me out, but now it looked like a kidnap as the rangers wouldn’t let me inform anyone of my detention. After about 30 minutes in the cell, they brought me out for a mugshot and then took me to a more isolated cell down the compound. About 30 minutes after, they would put me in a patrol Land Rover to the nearest police station. There, I made efforts to explain myself to the only officer who understood English, but he obviously wasn’t interested in my story. “Shut up!” he told me once and listened to the park officials who brought me instead.

UNDERCOVER: ONE WEEK AS A STAFF OF PALMCREDIT, WHERE I LEARNT THE ART OF DEFAMATION

FIJ’s Opeyemi Lawal spent one week undercover as a staff of PalmCredit, an online loan agency, to expose the “wilful disbursement of their loans to unsuspecting customers and their extreme tactics of defaming them when they don’t repay on time”. Opeyemi highlighted accounts of abuse and the pressure that leads lending agencies to weaponise defamation after landing a position as a loan collection specialist.

On the third afternoon, August 2, after our one hour break, Gerald came to announce that we needed to vacate the training hall, as the Chinese team wanted to hold a meeting there. He then took us to one of Easybuy’s halls in tens and asked us to sit with collectors who had also gone through the training and were duly employed.

What I saw in there was the exact opposite of all the boring lectures I had to endure. It was a madhouse filled with chaos and mayhem. Dozens of collectors screamed at the top of their voices.

Every single minute of the two hours we spent there, at least one collector was cursing and threatening to ruin a customer.

“I will ruin you. I will publish your details online. I will send it to all your contacts and nothing will happen,” a collector shouted at someone on the other end of the phone.

Every data privacy lesson Ikwele had taught us was invalid there, as collectors threatened customers in the presence of team leads who only walked about and did nothing. I couldn’t hide my shock.

The two ladies I was attached to asked if I had recovered money yet, when I answered in the negative, they told me that loan collectors who had passed the same training I was undergoing at the time actually send defamatory messages to customers but they do it discreetly.

“We do it in a way that the Quality Control team does not get to find out about it. This is because without the defamatory messages, customers will not pay, and if you don’t recover money, they will send you away,” one of the ladies explained.

They then told me to get multiple sim cards besides my main phone number so that I could use them to send these messages to customers when the need arose.

“See, once you get inside, you will know how the job works. Even the Quality Control team know we do this; they are only looking for who to catch red-handed,” the other lady said.

Having read stories and watched videos about the experiences of casual workers in Nigerian factories, Abimbola Abatta spent three days at Lucky Fibres Limited, the factory that produces carpets, rugs, and the well-known Lush Hair extension, putting herself in the shoes of their workers to see how well it would fit.

Faridah, one of the workers, said I must have earned N1500 daily for 20 days if I wanted to make at least N30,000 on payday.

“How hard can it be to make N1500 a day, considering all the work we did for the day?” I thought. Alas, I was wrong! You could work from morning until evening and only earn less than N1,000.

Sala had earlier told me during the recruitment process that depending on how hardworking I was, I could make between N1,000 and N2,000 daily.

But Faridah told me that making N2,000 a day was not impossible, but it was difficult. She said one could earn as little as N100 in a day.

“The work is stressful, but what choice do we have?” She said.

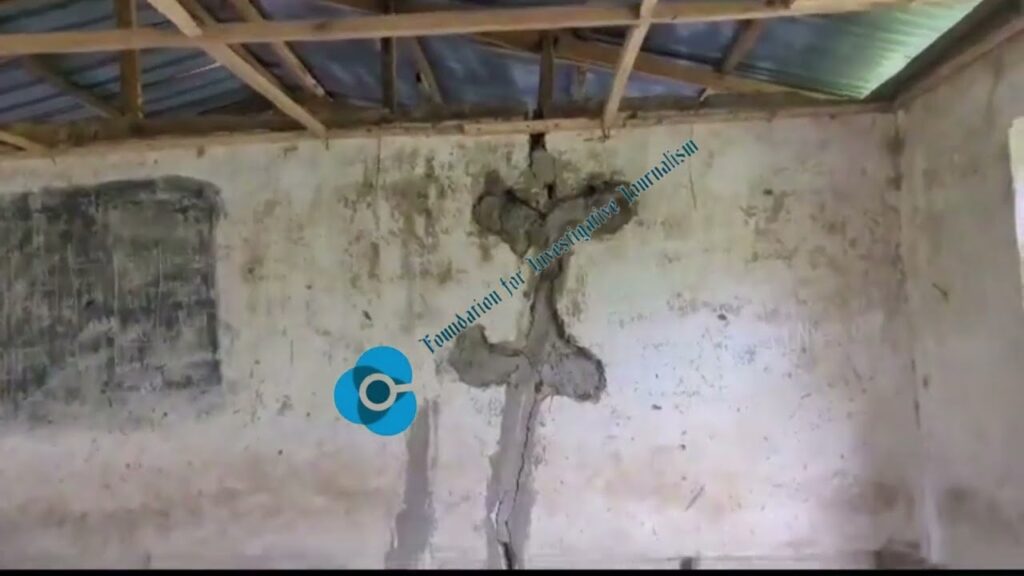

Two weeks before former President Muhammadu Buhari’s term ended, an office led by a former deputy governor of Lagos State transferred N147.1 million from the federal government’s coffers to the account of a restaurant to build classroom blocks and a skill acquisition centre in a Lagos primary school. However, FIJ’s Daniel Ojukwu would discover that there was no indication of construction at the designated site, and the restaurant was never eligible to receive funds from the government.

On October 6, 2023, FIJ visited the community in search of a school that fit the description on the contract. We found that there were about 72 primary schools in the area, and we checked what some of them looked like.

What we met was dilapidation, understaffing and ill-equipped classrooms.

Seven days later, we visited the community again to find if there were any skill acquisition centers or new classrooms in the area.

When we spoke to some of the staff of the government-owned schools, they told us on condition of anonymity that no one had been there in over a year to improve the quality of the schools.

“Help us tell the government to do something here,” one teacher told FIJ. “You can see around that this place does not have anything.”

When we showed the contract details to a headmaster, he said, “From what I can see here, this is unreal. There is no school like that here that has benefited from such a contract since I came here over four years ago.”

Multiple clients exposed Landwey, the gigantic real estate company owned by highly connected Olawale Ayilara, as a fraud in this piece written by FIJ’s Tarinipre Francis.

The story reads in part:

Fuelled by his multibillions, he operates a heavily-oiled PR machinery that has both Nigerian and foreign media under his grip, and funds a robust digital media team that periodically feeds the public with mouth-watering images of housing offers. To cap it all, Landwey and Ayilara possess deep-enough pockets to hire some of the most devious lawyers around, one proof of which is in the company’s final agreement with prospective clients, as can be seen here.

However, even when Landwey’s clients have tended to be negatively disposed to media interviews, they continue to scamper everywhere for help, including the DMs of FIJ and its founder, sometimes in the hope they can write about their plight without being named, initiate any sort of dispute settlement meeting or assist in putting a class action together.

HELLO BABA SCAMMERS WHO DUPE RANDOM PHONE USERS HAVE HEADQUARTERS IN ILE-IFE

Although there are scammers everywhere, FIJ’s Sodeeq Atanda’s investigation revealed that ‘Hello baba’ scammers, who call random users and request that accidentally sent airtime digits be returned and then pretend to show gratitude by offering spiritual interventions, have their headquarters in Ile-Ife, the spiritual capital of the Yoruba race.

On September 21, when I arrived in Ile-Ife, an okada rider told me that the scammers were everywhere in the ancient town.

“If you go to Iremo, you will see them. They are also at different hidden spots in Oke-Ayetoro, Iloro and so many other places. This is their headquarters. They are almost everywhere,” the okada rider explained.

In the course of this investigation, more than 20 residents told FIJ how the scammers carry out their trade.

In the Iloro area of Ile-Ife, one of the places mentioned by the okada rider, the scammers abound. FIJ found two popular spots where these scammers operate freely. The fraudsters rub their illegality on the residents’ faces and it has now become normal. Indeed, many residents know these scammers and what they do.

LAGOS ABATTOIR WHERE SICK, DEAD ANIMALS ARE SLAUGHTERED AND VETS TURN BLIND EYE

The Oko-Oba abattoir in Lagos supplies a significant portion of the city’s daily meat consumption, but part of the meat leaving the slaughterhouse daily was from sick and dead animals. This was a secret until FIJ’s Emmanuel Uti penetrated the abattoir and exposed its unethical practices. The story reads in part:

As I observed, young men rolled in lifeless cows on the familiar wooden carts I had seen on November 3. In a span of 10 minutes, at least 11 dead cows were wheeled in, each telling a tale of its own demise – wrinkles, dried skin, and darkened hues revealed that they died due to illnesses. What followed was a swift butchering of the animals.

OSUN COMMUNITY WHERE QUARRYING THREATENS LIVES AND HOUSES — AND COMPANIES DON’T CARE

In Iwoye, a rural community in the Egbedore Local Government area of Osun State, wealthy owners of quarrying companies ignore the cries of the locals, who suffer from illnesses and weakening residential and public buildings as a result of the companies’ detonation of explosives to break rocks at quarrying points close to private and public properties, endangering public and environmental health. Sodeeq Atanda investigated the operations of these companies and documented the impact on the environment and individuals.

On a sunny afternoon, Samuel Olaniyan was sitting in the balcony of his house. Without a prior notice, Slava, operating a blasting site less than two kilometres to his residence, fired an explosive. The explosive produced violent sounds that shook the stability of his building structure as usual. Powered by the same explosive, plumes of noxious smoke discoloured the atmosphere. The same explosive also presented a scene that could have hit Olaniyan’s family most horribly.

“One incident that has been edged permanently in my head: as they (Slava) have always done, they detonated an explosive at their site over there and it came with a fearful sound. You could see the dusts in the air. Surprisingly, I saw a piece of rock flying toward my house. I never knew my wife was at the gate, trying to open it. She was just lucky that the rock did not land on her head. If that had happened, I don’t want to imagine what would have happened to her,” Olaniyan, a pastor, told FIJ.

On this note, dear reader, we welcome you to a new FIJ year. We want to do more, and we hope to keep seeing you around.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.