Arriving at the Lagos Station of the Nigerian Railway Corporation (NRC) at Alagomeji, Yaba, to board a train to Ibadan, I walk into an old structure — with faded cream colour and weeds growing on it — to purchase a ticket at a waiting area.

The sight that greets me suggests that people of all ages and statuses use the train service, which began skeletal service on December 7, 2020. While some passengers stroll in to purchase tickets after alighting from their exotic cars and giving last-minute instructions to their drivers, others arrive at the NRC premises by commercial public transport.

After an NRC staff member measures my body temperature and another scans my back pack with a metal detector, with a means of identification and N5,000, I purchase a Business Class ticket to get aboard the train, scheduled to leave for Moniya, Ibadan, in 1hour 30minutes at 4pm.

Although persons not wearing facemasks are not allowed to enter the reception, those who enter still manage to ignore the functional pedal-controlled hand washing equipment by the doorway. In the waiting section, there is no observance of physical distancing. As more passengers arrive, the waiting room gets crowded, prompting officials to bring more chairs while they announce an apology through the public address system for the late boarding of the train.

WHY CAN’T RAIL TRAVEL BE CHEAPER THAN ROAD?

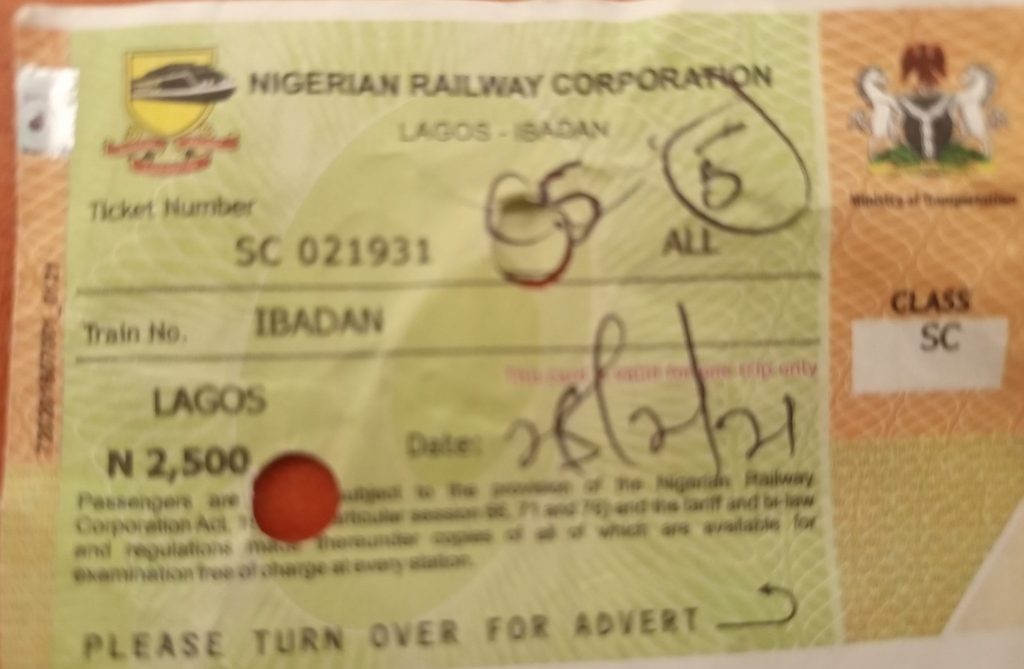

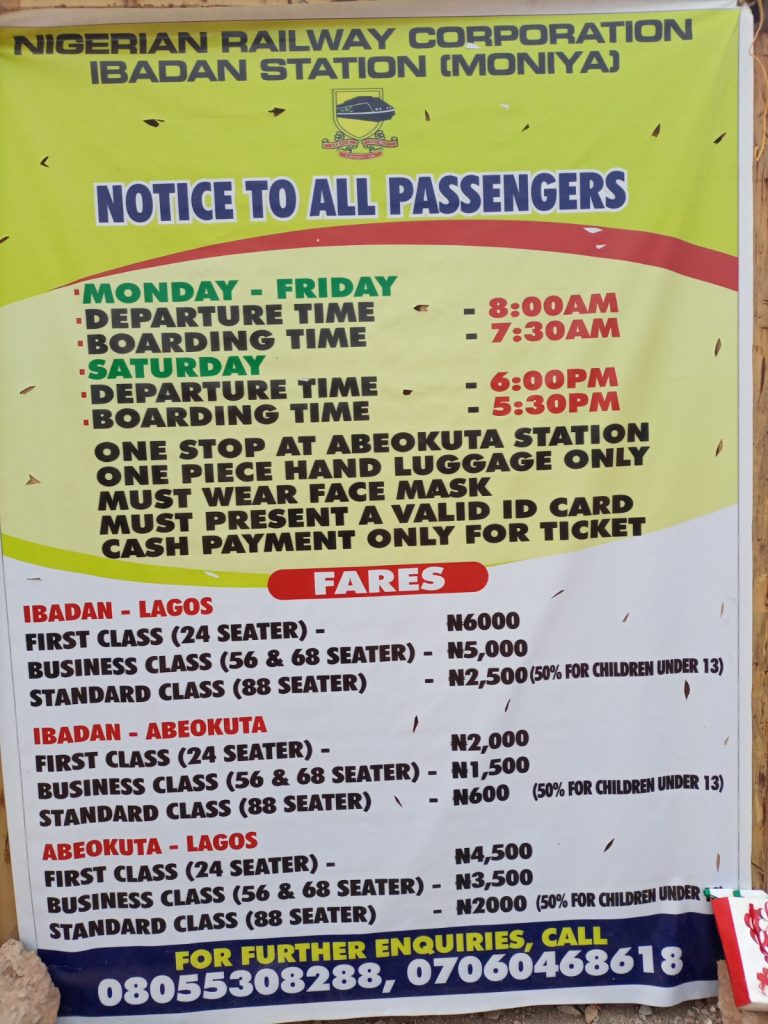

Sitting in groups, passengers complain about the high cost of tickets. While a Standard Class ticket costs N2,500, Business Class tickets cost N5,000 and First Class tickets costs N6,000. Rotimi Amaechi, the minister for transportation, said in 2020 that the ticket prices of the 156 kilometers Lagos-Ibadan rail were adopted from the 190 kilometers Abuja-Kaduna rail. Travelling to Ibadan by road costs about N2,500. Many hold the opinion that it should cost much less travelling to Ibadan by rail than by road.

“Are they giving us food?” one woman asks with a smirk.

“Maybe, we’ll see when we board,” another replies.

Other passengers wonder why ticket agents do not accept payment by card. A man says that he is left with trusting the point of sale (POS) agent to return his money after the first bank account he used was debited but the POS agent said the transaction was unsuccessful.

At 3:45pm, alongside other travellers, I walk to the terminus which is still under construction to board the eight-coach bullet-like train. Before getting aboard, luggage are scanned with metal detectors and officials guide passengers to which coach to enter, depending on their class of ticket.

WELL-LIT COACHES, FUNCTIONING ACs — IS THIS REALLY NIGERIA?

“I can’t believe this is in Nigeria,” one passenger says, as a female attendant wearing a black, knee-length gown taped with yellow ribbon at the edge of the long sleeve, directs her to her seat and offers to help the passenger place her bag on the overhead carriage.

The air-conditioned coaches are well-lit and fitted with two CCTV cameras each. The chairs are arranged to give enough legroom. The airconditioner works so well the coach gets too cold, prompting passengers to complain. Before adjusting the air conditioner, an attendant advises passengers to bring along cardigan when next they board the train. The restroom looks clean and the facilities in it work: It flushes; there is a handwashing basin with running water; there is toilet paper. However, I did not see soap.

THERE’S EVEN A DOCTOR ON BOARD

As the train rolls off to commence the 2hours 40minutes trip, which has just two stops in Abeokuta and Ibadan, a series of announcements comes through the public address system, informing passengers that a medical official is onboard to attend to emergencies and to keep their nosemasks on during the trip. Occasionally walking round to ensure compliance with Covid-19 protocol, attendants urge passengers to use nose masks and adhere to physical distancing rule in the Covid-19-induced sitting arrangement.

At Oshodi, Ikeja and Agege, I see traders display their wares on the rail track. Oblivious of the danger of being crushed, these traders hurriedly evacuate their wares on sighting the train. They rearrange them on the track when it passes.

Responding to questions about the train’s slow motion, an official onboard says the train has the capacity to run at 150 kilometres per hour, but because of traders who sell on the rail track, it runs at between 20 to 30 kilometres per hour to avoid a mishap. He says full speed will begin at Kajola. When the train’s operator begins running 16 trips daily on the double-track line, there is the risk of accidents if barricades are not installed.

FIRST CLASS BUT NO TEA OR REFRESHMENTS

About an hour into the trip, a passenger in a business class coach, asks an attendant when tea will be served.

“Not yet sir. We only have water,” she says.

The response moves the passenger to snarl and shake his head.

Business and First Class passengers get nothing in value that is commensurate with the cost of their tickets. The only visible and significant difference between the standard, business and first class coaches is that the standard carries more passengers than the other two. An attendant says refreshments are not served because of Covid-19 and because full operations has not started.

CATTLE HERDS BUT NO HERDSMEN

After 1hour 25minutes, we arrive at the Laderin station in Abeokuta. It is uncompleted like many of the stations we passed by. Instead of a five-minute stop, the train delays at the station for over 15 minutes. I later gather that an object placed on the track caused the delay. An arrest is made and the journey resumes.

The train’s speed increases after it leaving Abeokuta at 5:45pm. . I observe at least four herds of cattle grazing near the rail track. With no herdsmen in sight, there is the tendency for the cattle to wander to the rail track.

At 6:42pm, the train arrives the Moniya Station in Ibadan, again undergoing construction. The night is falling and the weather is dusty and dry. Around the station is a thick forest and the road leading to it is untarred. As passengers disembark from the train, some take pictures with the train in the background while others rush to board taxis.

“The ride was dope,” Deborah Oladimeji, a university student and singer, tells me.

It was her first time on a train.

The 156km double-track rail project running from the country’s economic hub to another southwest city is the first in West Africa. Financed by China with the Nigerian government providing counterpart funding, the $1.5bn project will be completed in April or May 2021.

DOES CORRUPTION ALWAYS HAVE TO ‘SHOW UP’?

The following day, I arrive Moniya station before sunrise at 6:15am to board the train back to Lagos. A tanker sprays water on the dusty ground at the station at 7am, as more travellers arrive and officials begin selling tickets. Tables and chairs are arranged in front of a 40ft metal container doubling as an office space.

Approaching a light-skinned male staff member assigned to sell standard tickets, I notice him pretending to detach the ticket from the booklet. Fidgeting, he lifts several leafs of fresh tickets still attached to the booklet, to remove the one he eventually gave me. The ticket he gives me is slightly ruffled. This official, possibly colluding with another, retrieved a ticket that was initially sold but not punctured. He probably will resell it.

Comparing the ticket he gave me with the one I was issued in Lagos the day before, I see a fault which enables double-dealing: the ticket sold at Moniya was not date-stamped like the one in Lagos.

Callistus Unyimadu, public relations officer of the Nigeria Railway Corporation, confirms that tickets sold at Moniya are not date-stamped. He tells me that unlike Lagos, Moniya station does not have full facility that will enable tickets to be date-stamped and that its staff are transported daily from Dugbe to Moniya.

“You know we are planning to launch e-tickets, but I will ask questions as regards allegations of double-dealing by our staff and get back to you,” he says.

Payment by card is not allowed. But it remains unclear whether the NRC made provision for the security of its staff who process huge amount of cash every day.

At 7:34am, the train arrives, travellers boarded and the trip to Lagos starts. One man with grey hair, whom I spoke to before boarding, describes the interior of the coach as “impressive”.

The last time he rode on a train was in the 80s. The Standard Class coach, which I am riding in, gives the same comfort as the Business Class coach I rode in the previous day. At 8:59am, we arrive Abeokuta. After an eight-minute stop, we set out for Lagos, arriving at 10:39am.

While the train ride was the first for some people, especially the young, for old people who witnessed the glory days of Nigeria’s railway service, it stirred feelings of nostalgia.

“I hope they can maintain this train,” the man with grey hair tells me. “This country can work for everyone if our leaders do the right thing.”

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.