Bruno Okere knew very little about loan apps until he was introduced to the world of debt. He never wanted to be in a position where a financial institution would defame him for a loan he took, until his financial fortunes took a hit.

“I never want to put up my property as collateral for a loan from a commercial bank because the chances of losing the property are high,” the 36-year-old trader said.

Okere runs a struggling real estate company that was at risk of going bankrupt. To cover shortfalls, he started borrowing from friends and relatives to keep his company afloat. But it was not a long-term solution.

The lure of a loan without collateral seemed appealing, an option he considered after watching several adverts of loan apps on YouTube. The loans vary from N1,000 naira ($1) to up to N500,000 naira ($500) with short repayment periods ranging from a week to two months, often with high interest rates.

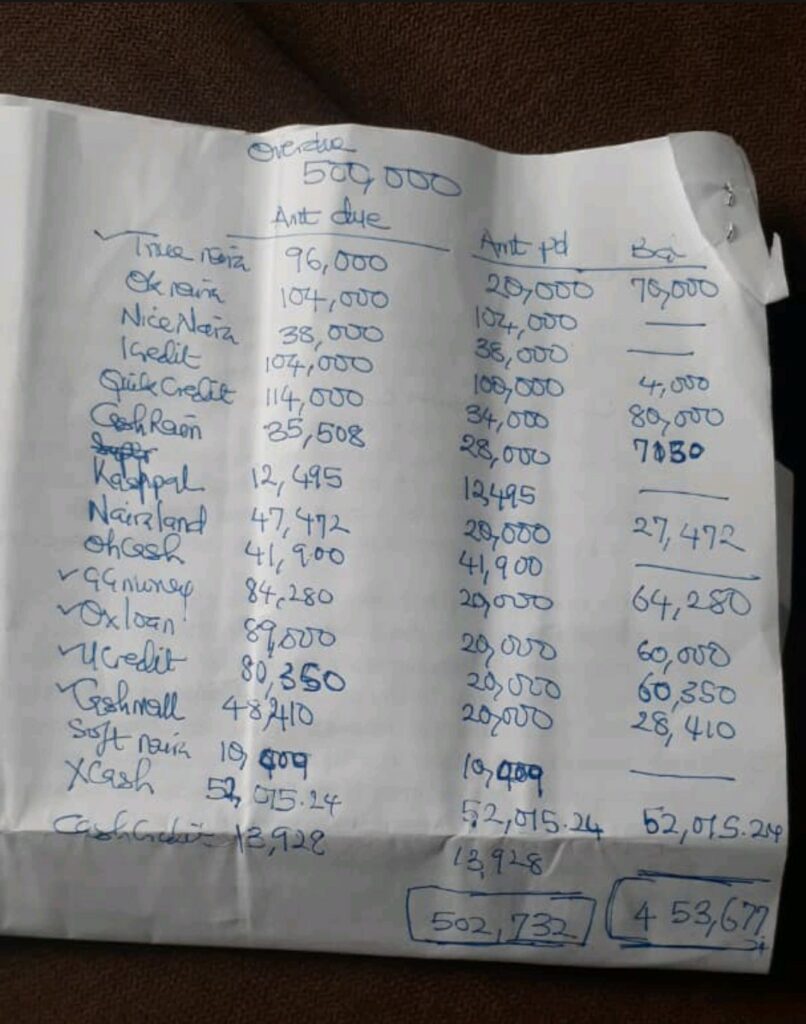

Okere’s plan seemed viable in the short term: Borrow money from multiple loan apps, invest it in his real estate company and use the profits to repay his debts when his business picks up.

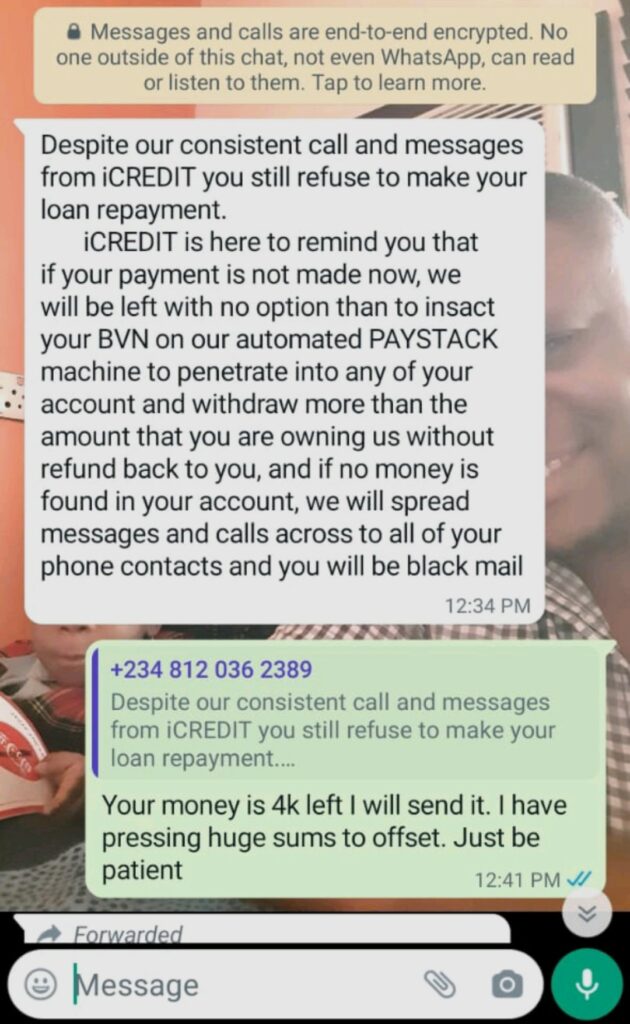

He went on a borrowing spree, and his first point of call was ICredit. He then proceeded to TrueNaira until he had borrowed from 15 different loan apps. The loan interest rates exceeded 60 percent a year, but Okere was desperate.

Despite the cash injection, his business venture did not prosper. Within two years, his debt had climbed to N956,409 ($2,702), and he was trapped: he was forced to borrow more money to pay off older loans.

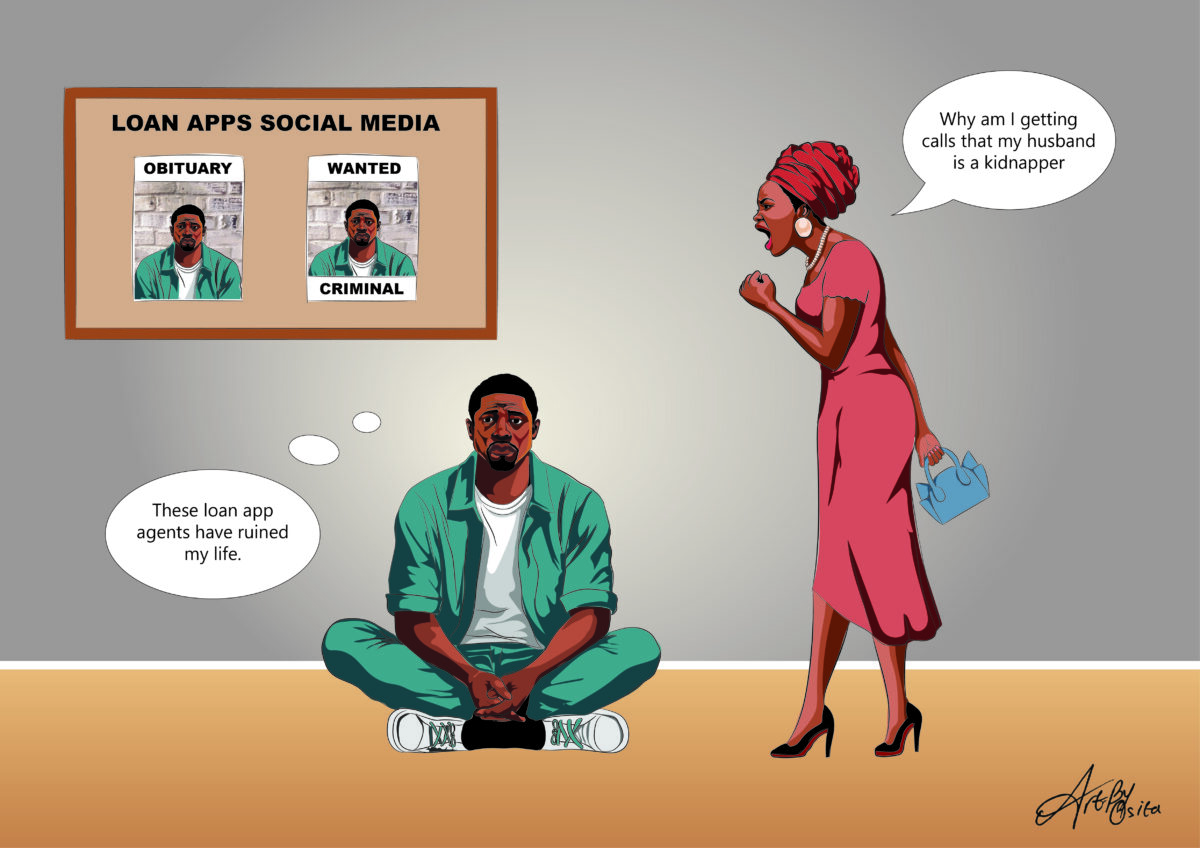

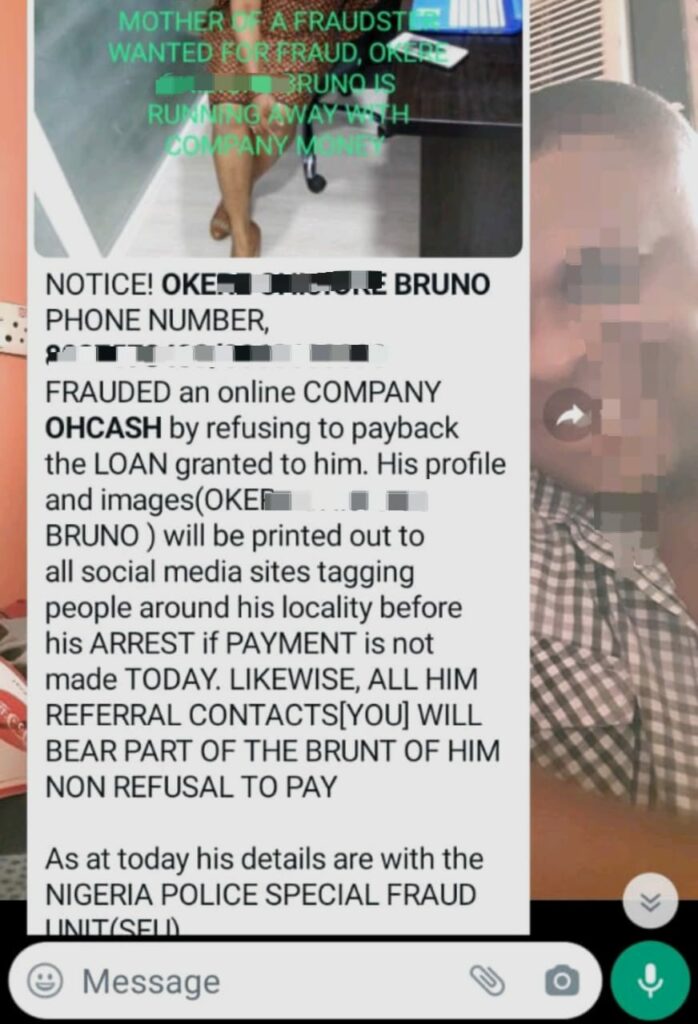

Okere answered the phone on a Friday morning in January, hoping it would be a new client looking for an apartment to rent. The call was from his mother, who was distraught after receiving a text message that labelled her as the mother of a fraudster whose son was on the run.

His explanation to his mother fell on deaf ears, as she scolded him for dragging the family name into the mud. His close friends, relatives, and colleagues also received these messages as often as three or four times a day from the lenders Okere had borrowed from.

Okere’s reputation was damaged; he was labelled a fraudster by several loan apps when he couldn’t meet the repayment deadline on their loans, and his clients also got these messages. The loss of his reputation set off a chain of events that almost culminated in the financial ruin of his business.

Okere was not alone, though, as thousands of Nigerian borrowers have been bullied by digital lenders, especially foreign-owned loan apps. Since digital lenders in Nigeria are not legally empowered to seize the landed properties of loan defaulters, they use the algorithms of their loan apps to compel borrowers to pay back their loans by damaging their reputations.

FRAGILE DEBTS, BIG LOSSES

Complaints about fintechs in Nigeria ranked number one in the 2022 fiscal year, according to Nigeria’s consumer watchdog, the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC). This accounted for more than half of the total number of consumer complaints.

After the coronavirus pandemic lockdown in 2020, commercial banks cut back on lending when small businesses and individuals needed cash. The lending companies stepped in to fill the gap.

One such digital lender is Fundy Loan, whose customers have complained of exploitation ranging from the illegal deduction of funds from their clients’ bank accounts to abuse by its loan recovery agents.

In late November 2022, Adi Festus, a 55-year-old diabetic, was in desperate need of cash to procure his prescriptions.

A pastor in a local church on the outskirts of the oil-rich city of Port Harcourt in southern Nigeria, Adi could barely get by on his monthly salary, and his ailment added to the financial strain. He applied for a N15,000 loan through the Fundy Loan app.

Adi only received N9,000 because his credit score was low, but when he couldn’t repay the loan within the stipulated payment schedule of one week, he started getting nasty threats from Fundy’s debt collectors. Soon, a poster with his face, labelling him an armed robber, was sent to his phone contacts, which included members of his congregation.

“I wouldn’t have taken the loan if only I knew how they collected it because the embarrassment was too much for me to bear,” he said. His comments mirror countless other complaints on the Facebook page for this particular lender.

Many aggrieved borrowers had resorted to social media platforms to call out their lender bullies.

James Ogbu, 31, first raised the alarm on Facebook after another loan company, De loan, published his picture as a fraudster. As is now the trend, they called and sent threatening messages to his family and friends.

Ogbu had only considered taking out a loan to help fund his brother’s study in the United Kingdom. “He had a scholarship, but it didn’t cover everything, and we were running around gathering funds so he could survive when he got there,” he said.

However, he cancelled his loan application process when the app only offered him a loan of less than N5,000 ($50) when he needed at least N500,000 ($500). The cancellation didn’t count. “I still got messages that I was owing,” Ogbu said.

When business partners started getting nervous about making deals with him, he knew he had to take strategic steps to clear his reputation. He first went and opened a case at the FCCPC headquarters in Lagos.

Although his case was assigned to an agent in the loan/lender taskforce division, the agent in charge warned him of the lenders’ tactics. “They change offices or hide. So it might take some time. That’s what the guy told me,” Ogbu explained.

With little prospect of success through the regulator, Ogbu thought that a public announcement on social media seemed the best step to salvaging his reputation.

According to Femi Adeoye, a loan risk analyst, Nigeria’s digital lending space is largely unregulated. He says the debt collection model of the apps threatens the civil liberties of the borrower.

“The Nigerian authorities have completely failed to address abuses by lenders,” said Adeoye, who is also a forensic accountant. “Most loan apps operating in Nigeria are below the radar. Some have no physical premises, or their email addresses on the Google store are incorrect or nonexistent.”

Last year, the FCCPC started cracking down on unregistered online money lenders by asking them to register with the FCCPC, which included providing basic company information.

Of the 173 digital lending apps legally registered in Nigeria, only 26 lending apps listed were owned by Chinese citizens. However, there are several unregistered lending apps operated by the Chinese still operating in the country.

READ ALSO: Palmcredit Threatens To Defame Woman Over N54,500 Loan She Did Not Ask For

A TECH BYPASS

Some illegal loan apps are operated by faceless individuals, which allows them to engage in heavy-handed tactics. For example, Fundy Loan, with over 20,000 downloads, and DeLoan, which Ogbu had borrowed from, are hosted on the Palmstore, a free mobile utility app like Google Play Store.

This pre-installed app store cannot be uninstalled, erased or deleted on Android smartphones made by Chinese phone maker Transsion Holdings.

Founded by Chinese billionaire Zhu Zhejiang, Transsion Holdings is Africa’s biggest smartphone supplier, making a name for itself by exporting cheap smartphones from China to developing African countries.

Today, about one-third of all the Android smartphones used in Africa are made by Transsion Holding. It also makes half the smartphones used in Nigeria. Its popular smartphone brands are Tecno, Oraimo, Infinix and Itel.

Most loan apps in Nigeria deploy AI in the lending business to profile borrowers applying for a loan, weed out ineligible borrowers and approve loans for people who meet their conditions without physical verification.

With less stringent regulations, Palmstore permits unlicensed loan apps banned for user abuse and harassment in Nigeria as Android Package Kit (APK). An APK is a file format outside of Apple Store and Google Play. It is compatible with Android devices that users can manually install on their devices from third-party sources.

If a user installs a loan app, they must accept the terms of service and grant permission to access sensitive data stored on the device. This is a major criterion if they must get a loan. Once access is granted, their algorithms collect data from a borrower’s device, which includes call logs, pictures, lists of installed apps, contact lists, social media history, location data, and text messages, which is encrypted and exported to the command and control (C&C) server of the loan app.

From this point, it is easier to monitor, threaten and blackmail debtors. Someone with a similar story of harassment is 26-year-old David Oseni, who fell behind on the weekly interest of N5,400 ($7) for a N30,000 ($39) rent loan he borrowed from Palmpay. Oseni said his phone got disconnected by the loan app after the debt got to N50,000 ($65).

The graphics designer was expecting a phone call to seal a contract worth N250,000 ($326) to design a company’s logo and offset his debts from the profits. However, with his smartphone locked, he couldn’t access the phone, and he also lost the data on the device.

“I abandoned the phone after two weeks of trying to get the Palmpay agents to connect and retrieve the data on my phone,” said Oseni.

In an email response to the claims of customers, Enitan Tanimowo, Palmpay’s public relations officer, said the company doesn’t engage in technological espionage to recover debts and would “like to emphasise that neither Palmpay nor any of our partners engage in blocking the smartphones of loan defaulters. “We place a premium on user data privacy,” she said.

However, Oseni, who is still hurting from the failed business deal and still has the debt hanging over him, blames his creditors for his ill fate.

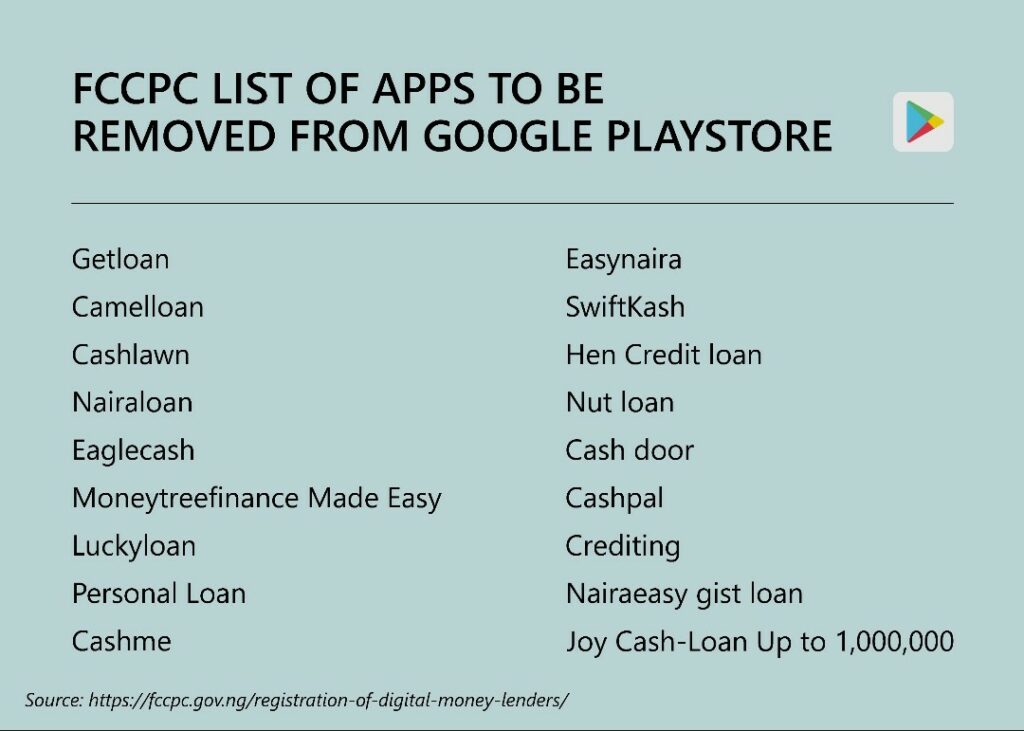

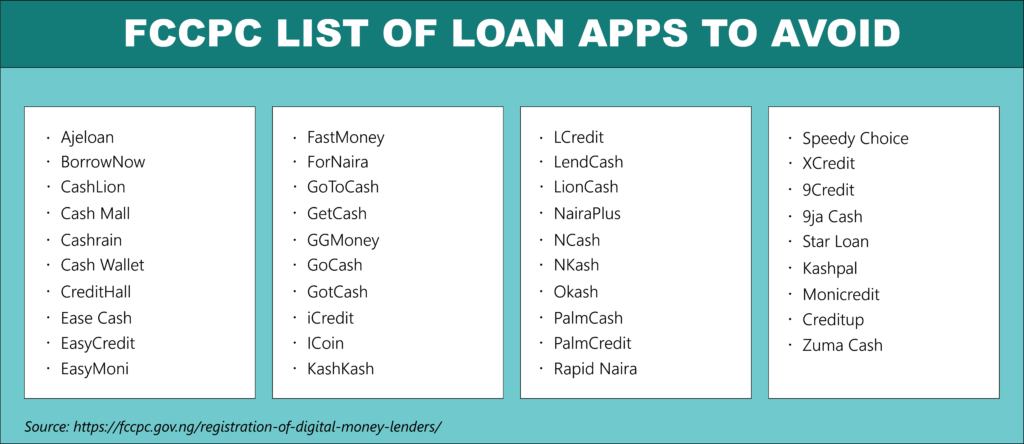

Most loan apps on Palmstore are also available on other ‘trusted’ third-party app stores and the Google Play Store. The Nigerian Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC), by the end of 2023, had asked the Store to remove 18 loan companies from the app store over regulatory infractions. The agency has also warned the public to avoid about 40 other loan apps.

Taiwo Ogunkola-Ogunlade, Google West Africa communications manager, said that Google had updated its personal loans policy in Nigeria to curb the menace of loan apps. Ogunlade said the platform now requires “developers to provide evidence of their compliance with regulatory standards”.

However, the only sanction the regulator can currently impose is to have the app removed from the Google Play Store.

TRACKING THE LENDERS

In March 2022, the FCCPC visited the offices of Lcredit, a subsidiary of Cashigo International, to investigate allegations of consumer rights violations. The staff of LCredit were alleged to have solicited and offered bribes to FCCPC officials, according to a lawsuit.

The loan app was subsequently removed from Play Store, and the FCCPC filed a lawsuit at the Lagos State High Court against LCredit for bribery, harassment and providing false information to its officials. The lawsuit implicated senior staff members of LCredit, including Liu Xu David(Chinese), Olayinka Akintade Ojomo, Emeka Odom and Lawretta Akwuru.

Most foreign-owned loan apps claim to have a physical presence in Nigeria. Our investigation casts doubt on this and indicates most predominantly operate online, with no proper place of business. They also need proper documentation, which makes it easier to hold them accountable for ethical breaches.

Incorrect and outdated information is still a challenge. In September 2022, we visited the locations of five lenders in Lagos. Only two were at their listed addresses at the time.

At the complex in Victoria Island where XGO Finance Limited, the owners of IMONEY, XCREDIT, and CREDIT9JA were located, security told us that the company had moved out during the pandemic.

The address for Windville Financials, owners of QCash/ProCash online address, also didn’t exist. According to a female receptionist at OTG House in Ikeja, where Palmcredit Loan was supposedly based, the company had relocated to another destination in Ogba.

QuickCheck Loan, which is run by Arve Limited and owned by Benjamin Benaim, a South African, was not at 13 Town Planning Way, Ilupeju 100252, Ikeja.

Since the faces of some of these unauthorised loan apps are unknown, we attempted to uncover the identities of the owners of LCredit.

The Corporate Affairs Commission database on beneficial ownership revealed that LCredit is owned by Cashigo International. The beneficial owners of the big lending firm are Cloudcone Technology PTE and Credit Tag Pte, all Singaporean companies.

Cloudcone Technology PTE is a subsidiary of WeShare Financial Group, owned by Hongyi Zhang, previously a director at an Indonesian lending company called Dana Rupiah.

WeShare Financial Group, headquartered in China, is the parent company of Cashigo International and Dana Rupiah, with other subsidiaries in Kenya, Vietnam, Mexico, Russia and the Philippines.

At its Lagos office at Churchgate Towers Victoria Island, a WeShare insignia is boldly displayed in the reception area.

An employee who only gave his name as Stanley Jacob, the IT and administration lead, spoke on behalf of his bosses, claiming he only had “ basic knowledge of how it (the lending process) works. “But I can refer you to customer service,” Jacob said.

However, Jacob also restricted these journalists from speaking to any staff, including the customer service or anyone from the risk management team, a department he said was charged with recovering company assets (money) from loan defaulters.

Meanwhile, the director’s address listed on the company’s incorporation files for Cashigo International belonged to Dana Rupiah, the Indonesian lending company.

It turned out to be an employee named Cecilia Ho who filed incorporation documents on behalf of the lending company in 2019. Ho’s LinkedIn profile shows she worked for Dana Rupiah between 2017 to 2019 as director of operations and joined Cloudcone Technology PTE as senior vice president. Presently, she works for Bixin Group, a blockchain and cryptocurrency company.

LOST GAINS

The network of companies involved in the ownership of LCredit further complicates the operations of this loan company. Without detailed financial reporting, the profit or revenue generated from its Nigerian subsidiary for its offshore affiliates is unstated.

Apart from the boom in unethical loan recovery methods by debt collectors in Nigeria, several loan apps may be involved in profit shifting, a scheming technique employed by multinational companies to reduce their tax burden by moving profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens, our findings show.

An example is Credit Tag Pte Ltd., LCredit’s beneficial owner located in Singapore, which moves its proceeds to Dana Rupiah in Indonesia and WeShare Financial Group, its parent company based in China.

On October 8, 2021, Dana Rupiah agreed with Credit Tag Pte, the beneficial owner of LCredit, to take payments for service fees from its lending business in Nigeria (and had transferred N495,535 by 2022). This payment is tax deductible in Nigeria, which has the effect of lowering its tax obligations locally since this payment is for services rendered to its immediate parent company.

WeShare Financial Group’s global lending earnings for 2021 show that its subsidiaries raked in N102.6 billion ($128 million), according to its financial disclosure documents. However, there was no breakdown of the amount generated from its Nigerian subsidiary or what it paid in corporate taxes.

In 2022, Credit Tag Pte transferred N495,535 ($500) to Dana Rupiah, its Indonesian partner, as payment for risk control work services, according to its financial report.

Similarly, findings show that Palmpay Payment Services, owned by Shenzhen Transsion Holding, the makers of Infinix, Tecno and Itel phones, through its Nigerian subsidiaries, has moved funds worth millions of dollars to companies in the UK and Hong Kong.

The beneficial owner of Palmpay Payment Services is listed on the CAC database as Transsnet Payment Services.

In 2022, through its subsidiaries – Dexintec UK and Dexintec Nigeria – Transsnet Payment Services transferred $20 million from Nigeria to the UK by converting cash into corporate shares and offered it as a gift to Dexintec UK Limited, its financial disclosure documents show.

The China-based phone maker realised $57.4 million globally from its “loan sharks” earnings in 2019, according to its financial statements.

Palmpay is yet to give a response to an email demanding explanations on why the company’s profits from its Nigeria subsidiary were converted to corporate shares as a “gift”.

The lack of comprehensive data that captures the financial activities of loan companies in Nigeria shrouds the full extent of potential tax dodging and profit shifting by these fintechs.

With over 200 apps in Nigeria, of which more than 100 are banned or controversial apps still operating, sometimes under different names and with unknown profit margins, it may be a long time before the implications of the losses are known.

“We only tax companies that derive an income of N25 million from their activities in the country,” said Abdullahi Ahmad, communications director at the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS).

But since “we don’t even know how much these companies make or where they are, we can’t know how much we lose in taxes,” said another source who pleaded anonymity.

Nigeria’s income tax remittance law stipulates that companies whose business in Nigeria is conducted through electronic or digital channels are subject to being taxed if they have a significant economic presence in Nigeria.

These journalists also contacted the loan companies and the FCCPC for a statement but had not received a response at the time of publication.

As such, it is unclear how much profit or tax the fintech makes or pays as corporate tax in Nigeria, the number of loan companies currently under investigation or the criteria for the previously delisted companies resurfacing on the approved list again.

In silence, harassment cases, cyberbullying of debtors and possible profit shifting by digital lenders in Nigeria may continue.

This project is supported by the Global Reporting Centre and the Citizens through the Tiny Foundation Fellowships for Investigative Journalism.

Subscribe

Be the first to receive special investigative reports and features in your inbox.